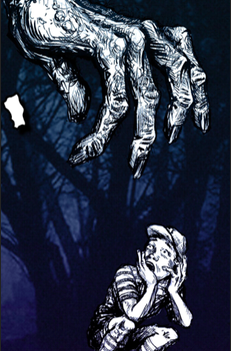

Illustration by Michael G. O'Connell Illustration by Michael G. O'Connell Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. (read by Kasey Lansdale) “I reckon some call us swamp people, you and I, but it ain’t ‘cause we’re different from them or anything. Not really. Sure, there’s tales, but plenty of folks has their tales. We’ve seen things, Berty. And heard things. And lived things. Me more than you, o’ course. And some of those things is jus’ so strange or terrifyin’ it’d be hard to speak on ‘em.” The ancient man took a deep breath and, as he did so, beat his pipe on the bottom of his shoe, then held up his hand and spread his fingers. “Look here, son, you and I are alike, right? But we’re different, too.” He stopped, raised his eyebrow, and looked at his young visitor. Albert did his part and regarded the timeworn hand in front of him and then his own. He compared the two. They were different, alright. His hand was barely as big as Mr. Sam’s pinky was tall, but not as small as his pointer finger—the one a gator had gnawed-off some fifty-odd years ago. Albert’s hand was small, pale, and a little pink and tan, while the other one was leather-like and dark as swamp water—at least on the top. The larger one was covered with veins like an uprooted oak. But both had thumbs and fingers—mostly—that could grab things, and both were filled with blood, gristle, and other bits that made them human. While Albert inventoried the differences and similarities, the way a nine-year-old might, Mr. Sam lit his pipe. “Heh. Heh. Heh. You’re a good boy, Berty. Smart. Strong, too, and you need to be strong.” That particular summer in the little town of Trembling had droned on, but it was almost over now. In a matter of days, Albert’s mother would be back, and he would finally get to leave his grandparent’s house for home and school and the possibility of new friends. For the last eight weeks or so, his visits with Mr. Sam had broken the fever of boredom like a cool drink of iced tea. The oppressive blanket of mugginess and heat kept the town slowed to a slug’s pace, its inhabitants residing mostly indoors or in the relative comfort of their shaded porches. Under Mr. Sam’s haint blue eaves, Albert had heard tales about the Great Swamp Fire of ‘25 — how the Indians and slaves used to secret themselves away in the Southern patchwork of black waters, mire, and prairie back when there were still Indians and slaves. He heard a more than a few dark tales about ‘folks gettin’ up to no good and terrifying visits in the night. Those particular accounts weren’t nearly as grisly as those yarns Mr. Sam told of his years with Jim in The Great War. Sometimes, Mr. Sam would reminisce with faraway eyes about how he met his wife, Carlotta, at the Salt and Pepper Club—a juke joint in Woodville over towards the Panhandle. But on that particular day, there was something brooding in his manner. Mr. Sam began slowly. “Some call it a tall tale, but the way I know it, these events chanced to happen almost a hundred years ago, and, for a long time, it was the wors’ thing that folks talked about in these parts. Well, I ‘spect that there ain’t no one left who could tell this story firsthand. You see, Berty, a bunch o’ white fellers up from Jacksonville had heard some strange tales when they was out huntin’ and drinkin’—tales about what might be living out in the heart of the swamp an’ if these stories was right, why, they figured with jus’ a little bit o’ killin’ they’d all be rich men.” “Berty, you sure you want me to go on tellin’ this one? It ain’t like the others.” Mr. Sam asked this last bit with a smile, but the skin on his face eased back until tight, making it more of a leer. “Why, this one might make you afraid to sleep by yo’self.” Albert, who had been sitting cross-legged on the porch with his back propped against the peeling clapboard wall, leaned in, elbows on his knees, in trepidation and anticipation. He hoped this story was going to be one of the good ones and was afraid that it might be. Mr. Sam took a long draw on his pipe, and when he exhaled, his face lost in an apple-flavored cloud of smoke. “Nine of ‘em went in, Berty. They was some of the meanest, hardest men from around these parts, and while they was more than a little rough around the edges, they might have been the best hunters and trackers to ever enter the great Okefenokee. They went in looking for any ol’ kind of clue. But they was hopin’ for more. An’ they was in there for almost two weeks and still hadn’t seen much o’ nothin’ but gators, panthers, and bears…” “Panthers and bears?” “That’s right, son. There used to be all kinds of creatures in that swamp. Oh, there still are a few bears and plenty o’ gators alright, but no one’s seen any panthers in these parts for the best part of fifty years.” “Now you stay outta that swamp, Albert O’Steen. Ain’t no place for little boys,” the old man’s wife added from across the porch. He stopped for a long minute that almost had Albert scared. Mr. Sam was beyond old, and he had been prone to slipping. One minute he’d be talking, and the next he would be slack-jawed, staring at the old hickory in his front yard. Drool running down his chin. He could be lost for the rest of the afternoon. There had been something mystifying about that tree, Albert thought, which drew his own eyes. The tree crawled with Spanish moss. The long, gray tendrils clung together as if afraid of the revenants of the other things that had hung from these branches in years past. “One day, just past noon,” Mr. Sam broke the spell, “the fellas broke for lunch. Now one was hungry because of the smell.” “The smell?” “Since morning, there had been a terrible smell that had been getting stronger all morning, but these men was hungry. And they wished they had more than biscuits and hoop cheese. They was all grousin’ about and cussin’ and whatnot when one o’ them fellas let out a ‘whoop’. He found a footprint. And not just any ol’ footprint, Berty. This one was bigger than anything any of them had ever seen.” “How big, Mr. Sam?” “Why, how big do you think it was yo’self, Berty?” His eyes dug deep into Albert’s thoughts. Both of Albert’s hands shot up, eager to prize Mr. Sam’s rheumy eyes from snaking their way too far into his brain. He held them about a foot-and-a-half apart, but Mr. Sam shook his head and the boy tried again. “Still too small, I ‘spect.” So Albert stretched his arms out as wide as they would go. Mr. Sam picked up his cane and moved Albert’s arms just a little closer together. “From the tales my own momma told me, I think that’d be about right.” “Whoa!” Albert exhaled the word, and his eyes grew as they did. “So now, these hardened fellas, rough as they were, started gettin’ excited—like girls in the schoolyard that had just seen one of them boys that’s in those teen magazines. But they got back to business right quick and began trackin’. Their hands gripped their rifles and pistols a little tighter, and the couple that brought swords checked to make sure they were still handy. These fellas knew what they was doin’, Berty ‘cause huntin’ was how you survived back then. Now, by this time, they’d been sloggin’ through dark water filled with snakes, and gators, and other things for the better part of the day, and it was gettin’ late. Some o’ them thought it best that they stop before it got too dark, but a couple o’ them boys wanted to keep movin’ forward, so as to get the deed over with as soon as possible.” “And while they was arguing, one of them, Stax was his name and the best tracker of them all, why, he just up and disappeared.” That got Albert’s attention. Mr. Sam pressed on. “The rest of his group didn’t notice until they heard him off in the distance. ‘Dammit, y’all! Quit squawkin’ like old washerwomen and git on over here,’ Stax bellowed.” Miss Lottie, who had been listening as she worked on her folding and pressing, sniffed loudly. “Well, that’s how my Momma told the story,” he said, but without looking over at his wife for fear of getting skivered by her steely eyes. Mr. Sam took his last sip of Nestea. His mouth had gone dry. He knew if he wanted more, he’d have to get it himself. He looked down at Albert and wondered if Lottie would let the boy in the house to fetch him some. The boy took that look as an opportunity to ask. “What happened to Stax? Was he killed? Did the others follow?” “Heh, heh, heh. Old Stax found hisself a second set of prints that had joined the first.” Mr. Sam grew silent, and his eyes began a slow movement out towards the old hickory tree, but he pulled at the wiry scrabble on his chin and continued. “Of course, now that there was two of ‘em, they all knew that they had to wait. The men were strong and brave, but those footprints were huge, Berty, and it was now dark. Heh. I’m sure none of them would admit to being afraid, but I imagine they was all shakin’ in their boots. So, you know what they did?” Albert shrugged. “Why, they made camp and decided to start again at first light. They ate their dinner and then, as they was arguin’ over a fire, the most horrible thundering started. And that crashin’ came right at ‘em outta the saw palmettos. ‘Twas a forkie that dashed past them, given’ them all a second or two to believe that it was only the young buck that had been out there all along makin’ all that ruckus. They was all laughin’ and thinkin’ about how they might be eatin’ venison for breakfast when something huge charged at them from the woods! GRWAAAAAA!!!!!!” Mr. Sam screamed and grabbed the boy. Albert almost jumped out of his skin. Miss Lottie giggled. “This thing was a giant. She was huge and covered in thick patches of coarse hair and smelled of rotten meat. That’s when the first o’ them hunters started shootin’, and within seconds, seven of them fellas had emptied their rifles, but the she-devil kept comin’. She was screamin’ and howlin’ something terrible. The other two now had their rifles, and the whole lot of them was firin’ and reloadin’ and firin’ some more, but she still kept comin’. And then…” And then Mr. Sam paused and looked over at Miss Lottie. Albert stole a quick look and saw that she had returned to her pressing. Then he looked back at Mr. Sam. “I ain’t so sure you should hear the details of what happened next ‘cause you just a lil’ peanut of a boy. Prolly best if I just give you the generalities.” “No, no, Mr. Sam. Please!” he begged. “Quiet, son!” Mr. Sam said in as loud as a whisper could manage. “You wanna hear this story or not? Heh, heh, heh.” Miss Lottie shook her head and mumbled something to herself. Albert put his hands together and mouthed the words’ please’ as if he were speaking to God. He did it as loud as he could without uttering a sound. “Alright, then Berty, but if the Booger come get you in your sleep…” Albert crossed his heart. Mr. Sam gave him a wink and continued. “So, the first hunter… why, he didn’t even have a chance. That ol’ giant come on him and grabbed him up with just one of her hands, and then…” he paused and looked hard at Albert. “she grabbed the fella’s head and she twisted.” “She jerked. Then there was a loud ‘POP!’ and off it came, lookin’ like meatball with spaghetti and meat sauce danglin’ as she pulled.” “She grabbed up a second feller and… POP!” He moved his hands like he was opening a jar of jelly. “She done it quick this time because the whole lot of them hunters was firing and reloadin’. That giantess musta known she had to move quicker because the bullets was startin’ to do their work. She scooped up two more o’ them fellas in one hand, and off came a head—POP! Then she used that fella’s head to smash the second. Both exploded like rotten pumpkins—little bits o’ bone and blood and gray matter flyin’ every which way. By now, that giantess was soaked in blood—so much of it her own—little geysers eruptin’ from her furry body in crimson fountains. There were heads and bodies at her feet, like a forgotten garden left too long in the sun. Before she went down, she snatched one last one and, POP! She dropped the body. It tried to run off but didn’t get far. The creature toppled like a big ol’ pine tree…” Mr. Sam whistled and seemed to watch as the colossus fell. “Thoom! It shook the ground mighty fierce. Some said that the trembling could be felt as far away as Hilliard.” He grew quiet again. “Say, Carlotta, do you reckon that’s how this place got its name?” Miss Lottie did not answer. She was stewing in her own special kind of fury, so the old man turned his attention back to the boy. “Berty, that hellcat wasn’t dead yet. She tried to reach out and grab another one, ‘cept she was mortally wounded, but she still had that last fella’s head. So she held it up and laughed. They say it sounded almost human, that laugh an’ as she laughed, she squeezed. The eyes exploded from their sockets as she roared. Much later, and they argued on this last bit, as men are prone to do. One said she was using some kind of rudimentary language—words and such,” he added the last for Albert’s benefit. “Another said it was just animal laughter mixed in with that frothy howl. Still others said it was an otherworldly wail of pain. Whatever it was, it took ten more bullets to finish her after she had hit the ground.” Albert’s eyes were as big as the bread plates on Grandmother’s Sunday table. Still, Mr. Sam kept talkin’. “Of course, they was all terrified—the ones that was left. Their hearts was pumpin’, and their hands was shakin’, and the hairs on the backs o’ their necks was as standin’ high as a cat’s back, but they got what they was after. They had their trophy.” He stretched that last sentence out and eyeballed Albert like he was trying to force the weight of what happened into the young boy at his feet. “They was all gonna be rich once they got her body out of the swamp.” Albert thought Mr. Sam looked like he had eaten an enormous plate of rotten Brussels sprouts. The old man started laughing. “Heh, heh, heh. Five men lost their lives that night, and now that Stax fella had hisself a big grin like Alice’s Cheshire Cat.” Albert felt like he was staring at one of Father Warren’s toughest math tests. He was completely lost. Mr. Sam caught on. “Berty, he was happy ‘cause he had to be thinkin’ that now he’d only have to split the rewards four ways.” “Can you believe that, Berty? Heh, heh, heh.” He laughed, but there was very little heart in it. Mr. Sam looked down at his hands and let out a deep breath. The boy still looked distressed. “Anyway, it was late. The moon had risen—just a fingernail, so there wasn’t much light. Lucky for them, one o’ them fellas still had a few wits about him and took out a length of rope to measure how tall that ogress had been. They say that other than all the hair that covered her body, he looked just like a woman—a very tall, very smelly, and very nekked woman.” Berty giggled a little. Mr. Sam eyed him and continued. “They just stood around the monster and stared at her. But then that fella—the one with the one functionin’ brain—scratched his head and said, ‘What if there’s more of them and they heard all that shooting?’ But they all just stood there gawkin’. They was men, and she was nekked and they hadn’t never seen a nekked lady that big before. That feller tried again. ‘Stax? Don’t you think they’d come a’ runnin’? I know’d I would.’ It looked like sense was staring to sink in. ‘And what do you suppose will happen when they see us carrying their wife or momma off like some sort o’ trophy?’ Now, that got ‘em all movin’. They gathered up all the guns and only the things that was dear to them, said a few quick prayers over their recently departed friends, and did their best to get out o’ that swamp as fast as their feet would carry them.” “I heard it took ‘em three days to find their way back out o’ that swamp. They ran and sloshed through mud an’ splashed through black water creeks, an’ they didn’t sleep a wink. When they finally did get out, you know what they did?” “Sleep?” “Nope.” “Take a bath?” “Heh, heh, heh. That might should’ve been what they did, but the first thing on their minds was to measure that rope. You know what they found out? That swamp woman was more than thirteen feet tall! That’s almost twice as tall as me, Berty! Heh, heh, heh.” He laughed, rubbed his chin, and pressed on. “Then the men finally did get some rest. Eventually they was ready to tell their story… well, o’ course no one believed they had tussled with a giant in the swamp. Some insisted it was only a bear, but others was thinking of the Skunk Ape or the Tall Man, or…” He leaned in really close to Albert and lowered his voice. “the Booger himself.” Miss Lottie sniffed extra loudly. “And maybe it was. Heh, heh, hehe. But the men? None of them was ever the same. And none o’ them ever went near the swamp again. The newspapers told the story, Berty, ‘course they did. And it was some kind of story, too! The Sheriff got mighty interested in where the other five fellas were, too, but it eventually died down. A few of the locals did listen and shared the story, but no one in their right mind believed such a tall tale.” Mr. Sam laughed to himself and repeated, “A real tall tale.” Albert had been holding on to his questions for too long. They burst from his mouth all at once. “Wow. Thirteen feet, huh? Twice as tall as you? I’m sure that you’ve been in the swamp. Did you ever see anything like that, Mr. Sam? Hmm? Do you think it really happened? Do ya?” A small smile was the only answer Albert received. And with that, Mr. Sam drifted off again, staring out at the old hickory. Albert did what he always did when Mr. Sam slipped. He waited and lost himself in thoughts of giants in the swamp. They sat that way for some time before Mr. Sam broke the silence with an answer for the boy. “There’s a lot o’ strange things in this world, Berty, and I don’t ‘spect we’ll ever know the whole of it. No, suh…” Mr. Sam let out a long, deep breath. He tried his pipe again, but the embers were dead. Albert felt like this was the end of something, so he waited for that something to happen. Mr. Sam pawed at his chin, bringing Albert’s attention back to the wiry chin stubble. When Mr. Sam spoke again, Albert missed the first part of what he said. “… of my story? Are you even listening, Berty?” “Well…” It was Albert’s turn to struggle. “I believe it’s true because my Momma told it to me,” Mr. Sam said. That seemed to be a good enough reason for Mr. Sam, but Albert pressed him. “I’ll bet she told you Santa Claus was real, too.” With that, Mr. Sam leaned forward, then heaved himself up and out of the chair. Albert had never seen the old man standing up or anywhere but on his porch, sitting in his rocking chair. He knew he was tall because Mr. Sam would often work his height into his stories, but Albert didn’t realize just how tall the old man had been. The boy had often wondered if the man lived out his entire life sitting in the rocker on that porch. When he stood, Albert figured Mr. Sam had to be taller than Artis Gilmore, the center who played ball for Jacksonville University. He watched the man as he eased his way toward the door. As he pulled it open, he said, “I know because my momma had to see for her own self. She paid a visit to those giants out in the swamp. She even knew one of ‘em.” Mr. Sam winked at Albert and laughed. “But just that one time. Heh, heh, heh.” Michael O'Connell has always been a storyteller but is relatively new to writing. A retired creative director and illustrator, he now spends much of his time writing and reading. His writing goals for 2021 were to get published and finish the first draft of his novel. Having succeeded on both accounts, this year he is focusing much of his time on editing and writing short stories and poetry, as well as illustrating his wife’s long-neglected children’s book. Originally published July 27, 2022.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLinda Gould hosts the Kaidankai, a weekly blog and podcast of fiction read out loud that explores the entire world of ghosts and the supernatural. The stories are touching, scary, gruesome, funny, and heartwarming. New episodes every Wednesday. |