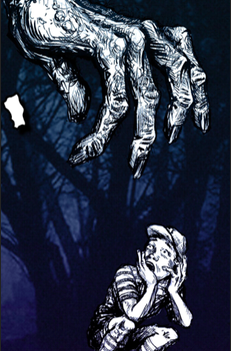

Illustration by Michael G. O'Connell Illustration by Michael G. O'Connell Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. (read by Kasey Lansdale) “I reckon some call us swamp people, you and I, but it ain’t ‘cause we’re different from them or anything. Not really. Sure, there’s tales, but plenty of folks has their tales. We’ve seen things, Berty. And heard things. And lived things. Me more than you, o’ course. And some of those things is jus’ so strange or terrifyin’ it’d be hard to speak on ‘em.” The ancient man took a deep breath and, as he did so, beat his pipe on the bottom of his shoe, then held up his hand and spread his fingers. “Look here, son, you and I are alike, right? But we’re different, too.” He stopped, raised his eyebrow, and looked at his young visitor. Albert did his part and regarded the timeworn hand in front of him and then his own. He compared the two. They were different, alright. His hand was barely as big as Mr. Sam’s pinky was tall, but not as small as his pointer finger—the one a gator had gnawed-off some fifty-odd years ago. Albert’s hand was small, pale, and a little pink and tan, while the other one was leather-like and dark as swamp water—at least on the top. The larger one was covered with veins like an uprooted oak. But both had thumbs and fingers—mostly—that could grab things, and both were filled with blood, gristle, and other bits that made them human. While Albert inventoried the differences and similarities, the way a nine-year-old might, Mr. Sam lit his pipe. “Heh. Heh. Heh. You’re a good boy, Berty. Smart. Strong, too, and you need to be strong.” That particular summer in the little town of Trembling had droned on, but it was almost over now. In a matter of days, Albert’s mother would be back, and he would finally get to leave his grandparent’s house for home and school and the possibility of new friends. For the last eight weeks or so, his visits with Mr. Sam had broken the fever of boredom like a cool drink of iced tea. The oppressive blanket of mugginess and heat kept the town slowed to a slug’s pace, its inhabitants residing mostly indoors or in the relative comfort of their shaded porches. Under Mr. Sam’s haint blue eaves, Albert had heard tales about the Great Swamp Fire of ‘25 — how the Indians and slaves used to secret themselves away in the Southern patchwork of black waters, mire, and prairie back when there were still Indians and slaves. He heard a more than a few dark tales about ‘folks gettin’ up to no good and terrifying visits in the night. Those particular accounts weren’t nearly as grisly as those yarns Mr. Sam told of his years with Jim in The Great War. Sometimes, Mr. Sam would reminisce with faraway eyes about how he met his wife, Carlotta, at the Salt and Pepper Club—a juke joint in Woodville over towards the Panhandle. But on that particular day, there was something brooding in his manner. Mr. Sam began slowly. “Some call it a tall tale, but the way I know it, these events chanced to happen almost a hundred years ago, and, for a long time, it was the wors’ thing that folks talked about in these parts. Well, I ‘spect that there ain’t no one left who could tell this story firsthand. You see, Berty, a bunch o’ white fellers up from Jacksonville had heard some strange tales when they was out huntin’ and drinkin’—tales about what might be living out in the heart of the swamp an’ if these stories was right, why, they figured with jus’ a little bit o’ killin’ they’d all be rich men.” “Berty, you sure you want me to go on tellin’ this one? It ain’t like the others.” Mr. Sam asked this last bit with a smile, but the skin on his face eased back until tight, making it more of a leer. “Why, this one might make you afraid to sleep by yo’self.” Albert, who had been sitting cross-legged on the porch with his back propped against the peeling clapboard wall, leaned in, elbows on his knees, in trepidation and anticipation. He hoped this story was going to be one of the good ones and was afraid that it might be. Mr. Sam took a long draw on his pipe, and when he exhaled, his face lost in an apple-flavored cloud of smoke. “Nine of ‘em went in, Berty. They was some of the meanest, hardest men from around these parts, and while they was more than a little rough around the edges, they might have been the best hunters and trackers to ever enter the great Okefenokee. They went in looking for any ol’ kind of clue. But they was hopin’ for more. An’ they was in there for almost two weeks and still hadn’t seen much o’ nothin’ but gators, panthers, and bears…” “Panthers and bears?” “That’s right, son. There used to be all kinds of creatures in that swamp. Oh, there still are a few bears and plenty o’ gators alright, but no one’s seen any panthers in these parts for the best part of fifty years.” “Now you stay outta that swamp, Albert O’Steen. Ain’t no place for little boys,” the old man’s wife added from across the porch. He stopped for a long minute that almost had Albert scared. Mr. Sam was beyond old, and he had been prone to slipping. One minute he’d be talking, and the next he would be slack-jawed, staring at the old hickory in his front yard. Drool running down his chin. He could be lost for the rest of the afternoon. There had been something mystifying about that tree, Albert thought, which drew his own eyes. The tree crawled with Spanish moss. The long, gray tendrils clung together as if afraid of the revenants of the other things that had hung from these branches in years past. “One day, just past noon,” Mr. Sam broke the spell, “the fellas broke for lunch. Now one was hungry because of the smell.” “The smell?” “Since morning, there had been a terrible smell that had been getting stronger all morning, but these men was hungry. And they wished they had more than biscuits and hoop cheese. They was all grousin’ about and cussin’ and whatnot when one o’ them fellas let out a ‘whoop’. He found a footprint. And not just any ol’ footprint, Berty. This one was bigger than anything any of them had ever seen.” “How big, Mr. Sam?” “Why, how big do you think it was yo’self, Berty?” His eyes dug deep into Albert’s thoughts. Both of Albert’s hands shot up, eager to prize Mr. Sam’s rheumy eyes from snaking their way too far into his brain. He held them about a foot-and-a-half apart, but Mr. Sam shook his head and the boy tried again. “Still too small, I ‘spect.” So Albert stretched his arms out as wide as they would go. Mr. Sam picked up his cane and moved Albert’s arms just a little closer together. “From the tales my own momma told me, I think that’d be about right.” “Whoa!” Albert exhaled the word, and his eyes grew as they did. “So now, these hardened fellas, rough as they were, started gettin’ excited—like girls in the schoolyard that had just seen one of them boys that’s in those teen magazines. But they got back to business right quick and began trackin’. Their hands gripped their rifles and pistols a little tighter, and the couple that brought swords checked to make sure they were still handy. These fellas knew what they was doin’, Berty ‘cause huntin’ was how you survived back then. Now, by this time, they’d been sloggin’ through dark water filled with snakes, and gators, and other things for the better part of the day, and it was gettin’ late. Some o’ them thought it best that they stop before it got too dark, but a couple o’ them boys wanted to keep movin’ forward, so as to get the deed over with as soon as possible.” “And while they was arguing, one of them, Stax was his name and the best tracker of them all, why, he just up and disappeared.” That got Albert’s attention. Mr. Sam pressed on. “The rest of his group didn’t notice until they heard him off in the distance. ‘Dammit, y’all! Quit squawkin’ like old washerwomen and git on over here,’ Stax bellowed.” Miss Lottie, who had been listening as she worked on her folding and pressing, sniffed loudly. “Well, that’s how my Momma told the story,” he said, but without looking over at his wife for fear of getting skivered by her steely eyes. Mr. Sam took his last sip of Nestea. His mouth had gone dry. He knew if he wanted more, he’d have to get it himself. He looked down at Albert and wondered if Lottie would let the boy in the house to fetch him some. The boy took that look as an opportunity to ask. “What happened to Stax? Was he killed? Did the others follow?” “Heh, heh, heh. Old Stax found hisself a second set of prints that had joined the first.” Mr. Sam grew silent, and his eyes began a slow movement out towards the old hickory tree, but he pulled at the wiry scrabble on his chin and continued. “Of course, now that there was two of ‘em, they all knew that they had to wait. The men were strong and brave, but those footprints were huge, Berty, and it was now dark. Heh. I’m sure none of them would admit to being afraid, but I imagine they was all shakin’ in their boots. So, you know what they did?” Albert shrugged. “Why, they made camp and decided to start again at first light. They ate their dinner and then, as they was arguin’ over a fire, the most horrible thundering started. And that crashin’ came right at ‘em outta the saw palmettos. ‘Twas a forkie that dashed past them, given’ them all a second or two to believe that it was only the young buck that had been out there all along makin’ all that ruckus. They was all laughin’ and thinkin’ about how they might be eatin’ venison for breakfast when something huge charged at them from the woods! GRWAAAAAA!!!!!!” Mr. Sam screamed and grabbed the boy. Albert almost jumped out of his skin. Miss Lottie giggled. “This thing was a giant. She was huge and covered in thick patches of coarse hair and smelled of rotten meat. That’s when the first o’ them hunters started shootin’, and within seconds, seven of them fellas had emptied their rifles, but the she-devil kept comin’. She was screamin’ and howlin’ something terrible. The other two now had their rifles, and the whole lot of them was firin’ and reloadin’ and firin’ some more, but she still kept comin’. And then…” And then Mr. Sam paused and looked over at Miss Lottie. Albert stole a quick look and saw that she had returned to her pressing. Then he looked back at Mr. Sam. “I ain’t so sure you should hear the details of what happened next ‘cause you just a lil’ peanut of a boy. Prolly best if I just give you the generalities.” “No, no, Mr. Sam. Please!” he begged. “Quiet, son!” Mr. Sam said in as loud as a whisper could manage. “You wanna hear this story or not? Heh, heh, heh.” Miss Lottie shook her head and mumbled something to herself. Albert put his hands together and mouthed the words’ please’ as if he were speaking to God. He did it as loud as he could without uttering a sound. “Alright, then Berty, but if the Booger come get you in your sleep…” Albert crossed his heart. Mr. Sam gave him a wink and continued. “So, the first hunter… why, he didn’t even have a chance. That ol’ giant come on him and grabbed him up with just one of her hands, and then…” he paused and looked hard at Albert. “she grabbed the fella’s head and she twisted.” “She jerked. Then there was a loud ‘POP!’ and off it came, lookin’ like meatball with spaghetti and meat sauce danglin’ as she pulled.” “She grabbed up a second feller and… POP!” He moved his hands like he was opening a jar of jelly. “She done it quick this time because the whole lot of them hunters was firing and reloadin’. That giantess musta known she had to move quicker because the bullets was startin’ to do their work. She scooped up two more o’ them fellas in one hand, and off came a head—POP! Then she used that fella’s head to smash the second. Both exploded like rotten pumpkins—little bits o’ bone and blood and gray matter flyin’ every which way. By now, that giantess was soaked in blood—so much of it her own—little geysers eruptin’ from her furry body in crimson fountains. There were heads and bodies at her feet, like a forgotten garden left too long in the sun. Before she went down, she snatched one last one and, POP! She dropped the body. It tried to run off but didn’t get far. The creature toppled like a big ol’ pine tree…” Mr. Sam whistled and seemed to watch as the colossus fell. “Thoom! It shook the ground mighty fierce. Some said that the trembling could be felt as far away as Hilliard.” He grew quiet again. “Say, Carlotta, do you reckon that’s how this place got its name?” Miss Lottie did not answer. She was stewing in her own special kind of fury, so the old man turned his attention back to the boy. “Berty, that hellcat wasn’t dead yet. She tried to reach out and grab another one, ‘cept she was mortally wounded, but she still had that last fella’s head. So she held it up and laughed. They say it sounded almost human, that laugh an’ as she laughed, she squeezed. The eyes exploded from their sockets as she roared. Much later, and they argued on this last bit, as men are prone to do. One said she was using some kind of rudimentary language—words and such,” he added the last for Albert’s benefit. “Another said it was just animal laughter mixed in with that frothy howl. Still others said it was an otherworldly wail of pain. Whatever it was, it took ten more bullets to finish her after she had hit the ground.” Albert’s eyes were as big as the bread plates on Grandmother’s Sunday table. Still, Mr. Sam kept talkin’. “Of course, they was all terrified—the ones that was left. Their hearts was pumpin’, and their hands was shakin’, and the hairs on the backs o’ their necks was as standin’ high as a cat’s back, but they got what they was after. They had their trophy.” He stretched that last sentence out and eyeballed Albert like he was trying to force the weight of what happened into the young boy at his feet. “They was all gonna be rich once they got her body out of the swamp.” Albert thought Mr. Sam looked like he had eaten an enormous plate of rotten Brussels sprouts. The old man started laughing. “Heh, heh, heh. Five men lost their lives that night, and now that Stax fella had hisself a big grin like Alice’s Cheshire Cat.” Albert felt like he was staring at one of Father Warren’s toughest math tests. He was completely lost. Mr. Sam caught on. “Berty, he was happy ‘cause he had to be thinkin’ that now he’d only have to split the rewards four ways.” “Can you believe that, Berty? Heh, heh, heh.” He laughed, but there was very little heart in it. Mr. Sam looked down at his hands and let out a deep breath. The boy still looked distressed. “Anyway, it was late. The moon had risen—just a fingernail, so there wasn’t much light. Lucky for them, one o’ them fellas still had a few wits about him and took out a length of rope to measure how tall that ogress had been. They say that other than all the hair that covered her body, he looked just like a woman—a very tall, very smelly, and very nekked woman.” Berty giggled a little. Mr. Sam eyed him and continued. “They just stood around the monster and stared at her. But then that fella—the one with the one functionin’ brain—scratched his head and said, ‘What if there’s more of them and they heard all that shooting?’ But they all just stood there gawkin’. They was men, and she was nekked and they hadn’t never seen a nekked lady that big before. That feller tried again. ‘Stax? Don’t you think they’d come a’ runnin’? I know’d I would.’ It looked like sense was staring to sink in. ‘And what do you suppose will happen when they see us carrying their wife or momma off like some sort o’ trophy?’ Now, that got ‘em all movin’. They gathered up all the guns and only the things that was dear to them, said a few quick prayers over their recently departed friends, and did their best to get out o’ that swamp as fast as their feet would carry them.” “I heard it took ‘em three days to find their way back out o’ that swamp. They ran and sloshed through mud an’ splashed through black water creeks, an’ they didn’t sleep a wink. When they finally did get out, you know what they did?” “Sleep?” “Nope.” “Take a bath?” “Heh, heh, heh. That might should’ve been what they did, but the first thing on their minds was to measure that rope. You know what they found out? That swamp woman was more than thirteen feet tall! That’s almost twice as tall as me, Berty! Heh, heh, heh.” He laughed, rubbed his chin, and pressed on. “Then the men finally did get some rest. Eventually they was ready to tell their story… well, o’ course no one believed they had tussled with a giant in the swamp. Some insisted it was only a bear, but others was thinking of the Skunk Ape or the Tall Man, or…” He leaned in really close to Albert and lowered his voice. “the Booger himself.” Miss Lottie sniffed extra loudly. “And maybe it was. Heh, heh, hehe. But the men? None of them was ever the same. And none o’ them ever went near the swamp again. The newspapers told the story, Berty, ‘course they did. And it was some kind of story, too! The Sheriff got mighty interested in where the other five fellas were, too, but it eventually died down. A few of the locals did listen and shared the story, but no one in their right mind believed such a tall tale.” Mr. Sam laughed to himself and repeated, “A real tall tale.” Albert had been holding on to his questions for too long. They burst from his mouth all at once. “Wow. Thirteen feet, huh? Twice as tall as you? I’m sure that you’ve been in the swamp. Did you ever see anything like that, Mr. Sam? Hmm? Do you think it really happened? Do ya?” A small smile was the only answer Albert received. And with that, Mr. Sam drifted off again, staring out at the old hickory. Albert did what he always did when Mr. Sam slipped. He waited and lost himself in thoughts of giants in the swamp. They sat that way for some time before Mr. Sam broke the silence with an answer for the boy. “There’s a lot o’ strange things in this world, Berty, and I don’t ‘spect we’ll ever know the whole of it. No, suh…” Mr. Sam let out a long, deep breath. He tried his pipe again, but the embers were dead. Albert felt like this was the end of something, so he waited for that something to happen. Mr. Sam pawed at his chin, bringing Albert’s attention back to the wiry chin stubble. When Mr. Sam spoke again, Albert missed the first part of what he said. “… of my story? Are you even listening, Berty?” “Well…” It was Albert’s turn to struggle. “I believe it’s true because my Momma told it to me,” Mr. Sam said. That seemed to be a good enough reason for Mr. Sam, but Albert pressed him. “I’ll bet she told you Santa Claus was real, too.” With that, Mr. Sam leaned forward, then heaved himself up and out of the chair. Albert had never seen the old man standing up or anywhere but on his porch, sitting in his rocking chair. He knew he was tall because Mr. Sam would often work his height into his stories, but Albert didn’t realize just how tall the old man had been. The boy had often wondered if the man lived out his entire life sitting in the rocker on that porch. When he stood, Albert figured Mr. Sam had to be taller than Artis Gilmore, the center who played ball for Jacksonville University. He watched the man as he eased his way toward the door. As he pulled it open, he said, “I know because my momma had to see for her own self. She paid a visit to those giants out in the swamp. She even knew one of ‘em.” Mr. Sam winked at Albert and laughed. “But just that one time. Heh, heh, heh.” Michael O'Connell has always been a storyteller but is relatively new to writing. A retired creative director and illustrator, he now spends much of his time writing and reading. His writing goals for 2021 were to get published and finish the first draft of his novel. Having succeeded on both accounts, this year he is focusing much of his time on editing and writing short stories and poetry, as well as illustrating his wife’s long-neglected children’s book. Originally published July 27, 2022.

0 Comments

Photo by Andrew Measham on Unsplash Photo by Andrew Measham on Unsplash Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. One time, when I was a kid, I was playing in the river when I noticed a tiny bottle resting next to a rock in the stream. On second glance, it looked like the bottle had a note inside. Naturally thinking of pirates and treasure, I picked up the bottle and pulled out the note. The paper felt old-fashioned, but it didn't look aged. I unrolled the note: HELP ME! My name is Melody and I'm locked in my room at 134 Pine Road. They locked me up because they think I’m mad. I'M NOT MAD. I’m different, but I’m NOT MAD. I’ve never hurt ANYONE. PLEASE SET ME FREE! Something about the big block letters, written in what looked like a shaking hand, made my heart race. For a moment, I considered taking the letter to the authorities, but somehow, it felt like it was too urgent for that. I decided I should go and check out the address to assess the situation. 134 Pine Road turned out to be a crumbling Victorian farmhouse surrounded by an overgrown field. It didn't look like anyone had lived there in ages. Just as I was starting to think that the letter was probably many years old, I noticed there was a dim, flickering light coming from one of the upstairs rooms. Could it be Melody? I ran up to the porch and pushed open the front door. The inside of the house was dark, the only source of light being the sunlight that managed to make it through the dust-covered windows. There was no light switch or any sign of electrical lighting, but there were some melted candle stubs. I took a few steps inside. As my eyes adjusted to the light, I looked around. Everything about the place screamed “abandoned.” Just as I was starting to think the upstairs light had been my imagination, I heard furious pounding coming from above. Was it a person or an effect of the wind? The pounding became punctuated by tiny cries of, “Help me! Help me!” Or was it my imagination again, creating faint words out of the wind’s howl? It sounded real enough to me, and I ran towards the rickety staircase. It looked a bit unstable, but I was a kid then and heedlessly decided it was safe enough. I now shudder to think of what would have happened if that staircase had collapsed as I ran up it, but back then, I felt enormously brave when I reached the upper floor. The pounding grew more insistent, coming from a door just down the hall. I still wasn't sure if it was a person pounding at the door or the wind, but then I heard a young voice scream, “HELP! HELP ME!” This time, it was unmistakably a person. I ran for the door and pulled it open. Nothing. There was no one at the door. My eyes were drawn to a table in the middle of the room that held a candle with a dying flame. I realized it to be the source of the flickering light I had seen outside. I peered around the dim room, nearly jumping out of my skin when I noticed a girl sitting on a threadbare bed against the far wall. She seemed too far away from the door to have been pounding on it just a moment ago. She had also become very quiet, in contrast to the earlier screaming. She looked to be about the same age I was at the time. In a place that was so gray and decaying, she was a splash of life and color. Her bright red hair caught your attention right away. She might have looked very alive, but she certainly didn’t look very happy. She looked thin and sickly, like she had been malnourished for a long time. She stared at me with wide green eyes as though she had spent years waiting for me specifically to find her. “Are you okay?” I asked her, closing the door behind me as I stepped into the room. “No!” she said immediately. “I want to go outside!” “Are you sure that's a good idea?” I asked. Obviously, she wasn’t being taken care of and would have to be removed from this horrible place, but it looked like she might be too ill to simply walk outside. “Yes!” she insisted as she stood up. “They’ve locked me in this room for over a year now! Please, let me go outside! That’s all I want!” “Wouldn’t it be better if I contacted the authorities?” I suggested. “I think maybe you need to be taken to a hospital.” “NO!” she yelled, suddenly panic-stricken. “I want to go outside!” I studied her for a moment. Her red hair hung in an unkempt tangle. Her body was dirty and so was the ragged nightdress that covered it. She was barefoot. While her body looked very pitiful, her face held the determined expression of someone who would never change her mind about anything. “You are Melody?” I asked eventually. “Yes,” she breathed. “Please, let me go outside. I want to be outside.” “All right, I’ll let you go outside,” I agreed. “Why don’t you put on some clothes? Do you have a coat or shoes?” “I’m wearing all the clothes I own,” said Melody. “You mean just that nightgown?” “Yes,” she said. “They say I don’t need clothes if I’m not going to be outside.” “Why don’t they want you outside?” “I told you in the letter — they think I'm mad.” “Why do they think that?” I asked. “I’m not like the other boys and girls,” she said. “I’m different. They think that’s madness. I’m not mad. I know I’m not mad.” “Is ‘they’ your family?” I asked, and Melody nodded sadly without taking her wide eyes off me. “And does your family really live in this ancient place? It's practically falling apart!” “I want to be free!” she insisted, ignoring my question. “You can understand freedom, can't you? Please, set me free!” “Okay, I’m setting you free,” I said and I pulled open the door. Melody ran forward and threw her arms around me. She kissed me on the cheek, her lips ice cold against my skin. Then she rushed through the open door and bounded eagerly down the stairs. I chased after her, barely keeping up. Just ahead of me, she ran through the front door, laughing with childish glee as she made it outside. I ran through the door after her. She was gone. The field surrounding the house was now just as deserted as when I had arrived. I called her name, but there was no sign of Melody. It was as if she had vanished into thin air. As I stood there, looking around in confusion, an old man appeared, walking towards me. “Who are you?” I asked him as he approached. “I’m the caretaker,” he said casually. “You’re looking for Melody, aren’t you? She just disappeared, right?” “Yeah, how did you know?” “It’s always the same story,” the caretaker explained. “Someone finds a note in a bottle and it directs them to come here. They meet Melody in her room and feel sorry for her. They let her out. Later, someone else finds the same note in the same bottle. When the next person comes here, Melody is back in her room, once again waiting to be rescued.” “Why does she end up back in there?” I asked, trying to make sense of what the old man was telling me. “Because that’s the room where the poor girl died back in 1890,” he said, and a shiver ran down my spine. “She was only eleven years old. Every now and then, her ghost entices people to let her out, but it seems that her spirit can never quite escape the room that imprisoned her in life.” Matthew McAyeal is a writer from Portland, Oregon. His short stories have been published by "Bards and Sages Quarterly," "Fantasia Divinity Magazine," "cc&d," "The Fear of Monkeys," "Danse Macabre," "Scarlet Leaf Magazine," "Bewildering Stories," "Tall Tale TV," "Fiction on the Web," "Quail Bell Magazine," and "MetaStellar." In 2008, two screenplays he wrote were semi-finalists in the Screenplay Festival. A version of this story was published by "Fantasia Divinity Magazine" in "Issue 22, May 2018" and "Echoes of the Past: 2018 Anthology." It has also been published by "Bewildering Stories," "Tall Tale TV," "Scarlet Leaf Review," "Short Kid Stories," and "Metastellar." Originally published July 19, 2022.  Photo: Dima Pechurin on Unsplash Photo: Dima Pechurin on Unsplash Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. "Mommy..." "Yes son?" He looks at her, stares at her. "Could you close the closet door?" he whispers. She smiles. He thinks her teeth, too sharp, too sharp in this pale light. "Of course, son. Can't have the Boogie, Boogie Man come out of the closet, and steal your soul." She goes to the closet door, closes it to a crack, hand still on the knob, turns to her son with that same smile, winks, closes the door completely with a thud. "Thank you," he whispers, laying back as his mom goes to the door, goes to the door on her way out, turns off the light, still smiling, still her son looking at her, staring at her. He is now alone, in the dark, eyes open, then close, open, then close like the closet door. Then open, and so is that closet door, he sees, and he doesn't want to look too hard at it, doesn't want to stare, 'cause how did that door open on its own, why can't he just be left alone, no lectures, he's tired of learning, knowing. The fiend stands in the closet doorway, looking, staring at the boy, mocking in every way. "So little boy, boy, what shall we learn tonite," the fiend asks, its voice full, but behind it, speaking, always behind the speaker, in the closet, tucked away in another dimension. "It's just that," the boy says, "it's that," he continues, voice low, looking, staring, "the job's so hard, very difficult. I don't know, I just..." "None of us ever knew," the fiend's lips moving, voice coming from behind him, PERHAPS AT THAT FAR DISTANCE SCREAMING yet now barely heard. "But it's the way of the world, little boy, little boy. 'Accept and be glad', sayeth the Lord." The boy looks at the door his mother exited from, wishing it was the door she had entered from, at least she would be in the room with him now to say goodbye, but she isn't, she's thinking her thoughts far away, far away, not knowing she's going to lose and gain a son at the same time this night. "All us Boogie Men were once children, and all us Boogie Men will be children once again," the fiend says. "I'm tired of souls, little souls for breakfast, fears for lunch, dreams for dinner. Come, boy, little boy, I've taught you my ways, spells, take my place, nightmare, know my world. I just want a voice for once, one close at my side." The boy, looking, staring, accepts, trades places, and the first soul he has that day, for breakfast, instead of cereal, is his mother's son's imposter. Todd Sullivan currently lives in Seoul, South Korea, where he teaches English as a Second Language. He has had more than two dozen short stories, poems, essays, and novelettes published across five countries. He currently has two book series through indie publishers in America. He writes for a web and play series in Taipei. He founded the online magazine, Samjoko, in 2021, and hosts a YouTube Channel that interviews writers across the publishing spectrum. Originally published July 12, 2022  Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. Young Joseph watched as his mother approached the dining table with a bundle of cutlery and three plates in hand. It was their weekly take-out night and rotisserie chicken combos had just been delivered, but Mom still insisted they eat with proper dinnerware. The smell made Joseph’s stomach grumble. She placed one plate down for him, another for herself, then paused. “I don’t know why I…” She sighed. “I don’t want to hear about it tonight, Joey. Not a word.” Mom turned and headed back to the kitchen with the one spare plate. A clang of dishes rang out. I never say anything, he thought. Not when you still put your clothes to only one side in your closet, or even when you avoid sitting on the far right of the couch. Joseph took out the various pieces of dinner and arranged them on his plate alone. It was four years since his father had disappeared. Joseph had been only five. Few memories had stuck since then. He could still see the winter night he disappeared. He’d been at his bedroom window looking down at his Mom, who was waiting out front of their split-level bungalow in the cold, wearing a parka over her blue pajamas. Her skinny legs had shivered for hours until they just stopped, giving up long before her worries did. Tears collected snowflakes as they travelled down both cheeks. Some memories were even smaller, like fragments. Withering orange peels left on the coffee table, rotting under sunrays from their bay window. A coffee mug spinning in the microwave, then forgotten about. The revving of his father’s red sports car in the driveway until plumes of smoke bellowed out the back. Even his face was blurring. Blonde hair, rough skin. Pictures around the home were sparse after Mom put most away in storage. That voice though, gruff and dry, still rang through in Joseph’s mind. And it said just one phrase over and over. “Beware the Whirling Bone Machine, Joey. Don’t let it catch you.” After eating, Joseph helped clean up, bringing their take-out containers to the kitchen while she collected used cutlery. He pushed the peddle of the garbage bin down with his right foot and tossed one of the remaining bits of carcass in. A bone fell to the tile flooring. “One more for the bone machine.” He picked it up threw the bone in, hearing a clunk. “What did you say?” He spun to see her at the doorway. “What? Oh, Mom. Nothing, I—” “You better not be talking about what I think you’re talking about. That stupid saying from you-know-who.” Those words were banned. Joseph blamed himself for causing Mom to go to such extremes, asking her one too many times what they meant until she couldn’t take it anymore. “Sorry, Mom.” He gazed up at her eyes. They were blue like marbles, so unlike his dad’s brown eyes, and so unlike his own. “I didn’t mean to upset you.” “It’s okay.” She bent down to match his height. “If that man were here now, I’d straighten him out for ever scaring you with that nonsense. Let’s hope I never find him.” But you won’t. Joseph knew Dad was dead. In that moment, he wanted to just say it out loud and relieve her of having to hide it any longer. It was Mom’s words that confirmed it last Easter. After being punched in the gut by his cousin Billy, both boys were sent to separate rooms for playing too rough. Joseph had snuck back out to apologize but instead overheard her, his aunt and uncle openly discussing what she had done with his ashes. He slunk away before they noticed him peeking out and drove his head into a pillow to cry without making a sound. He let Mom walk out of the kitchen without saying anything more, allowing the lie to continue. Like how Santa Clause and the Tooth Fairy were still real. It seemed to make her happy, and that was reason enough for him to continue with the ruse. After Joseph slipped into bed later that night, Mom looked in from his bedroom doorway. “Get some sleep. I don’t want you late for school again.” “Okay, Mom. Love you.” She closed the door behind her. Joseph tucked himself tight under the sheets, palms beginning to sweat. His father’s words stuck on repeat as he lay there. Nightmare fuel. With just a night light on, he focused on the stipple ceiling to count the number of shapes he could find. Last time he felt frightened, it took finding about thirty-five distinct shapes before falling asleep. Beware the Whirling Bone Machine, Joey. Don’t let it catch you. Don’t let it… catch… you… Consciousness slipped away. Joseph was alone, standing in a dark, vacant parking lot. At first, there were no lights at all. Even the sky was starless. Then, a floodlight turned on somewhere above him. Something was out there, blanketed in the surrounding darkness. It approached with the faint sound of metal-on-stone, like a large object being pushed along the ground. It grew louder, soon accompanied by the clanking of chains. Joseph’s own quickening heartbeats joined the cacophony. The Whirling Bone Machine. With unseen propulsion, it slid under the flood light and cast him in a shadow. It was as a carousel-like contraption, like the ones he rode at carnivals. But this one was different. Joseph could make out splashes of crimson and ivory as it spun. Its rotation slowed after stopping just a few feet from him. He could now see the collection of ribs, femurs, skulls, and spines that were fixed to rusted poles with coarse yarn. Atop the makeshift seats were figures donned in black cloaks. They whispered in tones he could not understand. Two of them pointed at Joseph, then jumped down and approached. He felt cemented in place by fear, unable to run as the figures flanked him. They both grabbed an arm each. Their fingers penetrated his skin, rummaging underneath for bones. More bones for their infernal contraption. They pulled. Harder. And harder. He awoke. Joseph was damp from head to toe, sheets clinging tight to his pencil-like frame. After giving his heart a moment to slow, he pulled the covers down and went to his dresser to change. While pulling a new shirt over his head, Joseph contemplated telling his mother of the nightmare. Though, she had made it clear to not speak of it. She can’t help me. Nobody can stop them because they move in dreams. Maybe she couldn’t help Dad either. That’s why she doesn’t like talking about the bone machine. He let this thought play out, giving contemplation to various ways which he seemed like his father. Something that connected the bone machine to them both. Same last name? Same eye colour? Same house? After an hour of ruminating on this, sleep slowly crept over him. Phys-Ed followed lunch. For mid-October, the air was still warm enough for all students to be outside. Today, the coach had them begin with a run. Joseph pushed himself while sprinting to pass others around the school’s quarter mile track. His new shoes, donated to him by a member of Mom’s Facebook group, were laced up tight. Joseph had complained to her about his joints with the old shoes, something she swore he was just parroting after hearing shoe store employees suggest the same thing. But this new pair quieted those joint pains. He got by the other usual stragglers first. Joseph barreled forward during the straight sections of the track, passing other kids one-by-one. The leaders were just ahead. If I can be faster than them, I’ll be able to outrun the bone machine too. While coming around the final stretch, he felt his right foot land on something other than asphalt. A pebble, or rock. Joseph slipped, tumbling toward the outside of the track. When he stopped, he was flat on the ground and partially off the outer lane. Other kids stampeded around him, one knocking their shin into his side. Nobody paused to help him up. Grass stuck to his bare shins as he tried to find his footing again. He planted his right foot and a spike of pain shot up. Joseph yelped, then was breathless. Somewhere in the distance, Coach Marley asked if everything was okay. Joseph drew in air through the anguish and managed a more drawn out scream this time. His coach’s voice neared, as did other students, but Joseph was losing track of his surroundings with the radiating pain. One girl said the word ‘ambulance’ and he wanted to tell them not to bother, as Mom would be pulled away from work. Though, he couldn’t talk or do anything other than scream. With teary eyes, he didn’t notice the flashing lights approach until the ambulance was through the school gates and weaving in their parking lot. “The kid just stumbled,” he heard Coach Marley say to the paramedics as they leapt out of their vehicle. Getting moved to the stretcher hurt. Being pushed inside the vehicle hurt more. Every little jostle sent bolts of electricity through his foot. No, he was able to think for a second. Not my foot. My ankle. “I’ll call his mother,” said his coach as the ambulance doors slammed shut. During their drive, the paramedic stationed back with Joseph asked the same questions over and over. Easy ones, like what’s his birthday and what his full name was. While Joseph was still having trouble talking, he did manage to squeak out the answers. The ambulance slowed and took several turns. Joseph noticed a red sign that read, ‘EMERGENCY.’ The paramedics wheeled him in through the doors, passing curious onlookers who were walking out. Inside, the questions kept coming from staff and nurses. His coach arrived minutes later to begin some of the paperwork that had been stacking on Joseph’s stomach. While working through several details with Joseph, Coach Marley’s attention was caught. “Misses Langdon! Over here!” Mom flung into view from behind his stretcher like a speedboat. “Oh my god, oh my god, what happened, Joey?” “My shoes slipped. I do like them, Mom, but I slipped and hurt my ankle. The right one. It feels broken.” “My poor boy.” She placed both hands on Joseph’s cheeks and kissed his forehead. Then, she turned her attention to the crowd of adults for a briefing. Time continued to go by in waves. Waiting took hours. Getting shuttled around was just a few minutes. Getting scans were painful, he had to contort and stay still, the pain grew stronger than ever. He felt every second crawl by. Doctors diagnosed a break just above his right ankle. They knocked him out while setting the bone back in place and applied a cast. A nurse, young and smiley, helped keep him feeling comfortable as day turned to night. She had said her name once, but Joseph missed it in his haze. It was sometime after dinner when a doctor assigned to him, Doctor Cordon, returned with many documents in hand. The man pulled a chair up beside Joseph’s bed, which squeaked when taking on the man’s hefty weight. Mom leaned in to hear their conversation from across the room. “How do you feel?” asked Doctor Cordon. Joseph looked down the bed. Television glare illuminated his exposed toes. They poked out the end of his cast; they were plump and deeply discoloured. He tried to wiggle them, but they didn’t move. “Better now. Just sleepy.” Doctor Cordon shot a brief grin. “Joseph, before your accident… did you have pain in your foot?” “Sometimes, maybe. I’d complain about my joints, but Mom said it’s just because I’m too skinny.” “What other joints? Anywhere else, other than your right foot?” “I guess. Yes, sometimes here.” He pointed to his right knee. The doctor motioned Mom out the door, leaving Joseph attended by the young nurse. She served him banana-flavoured ice cream. Mom re-entered sometime later, looking pale and as if she’d been recently crying. Doctor Cordon followed close behind. His large figure partially blocking the entrance, which he leaned against with papers in hand. “What’s wrong Mom?” “Joey,” she said. Her words struggled to escape through trembling lips. “It turns out, this is no accident. You’re actually sick.” “Sick? Because of my ankle breaking?” “No, no. This is a special kind of sickness that made your ankle brittle enough to break. In fact, you helped the doctors here spot it because of your accident.” “What is the sickness called?” Mom looked back at Doctor Cordon, who approached, but she put up a hand. “Cancer.” I know that one. He recalled signing a card at school for a teacher with cancer. She never returned. All he could muster was an, “oh.” “I’m sorry, I really am, Joey.” She angled down to hug him in his hospital bed. “We’re going to fight this, though.” “I’ll be okay,” he muttered into Mom’s shoulder as she whimpered. Though, that was a lie. They could call this disease whatever they’d like. He knew it was really the bone machine just wearing him down. An older nurse, one who took over for his young nurse, cleared him for release the next day. Mom pulled into the Emergency entrance circle with their white sedan and moved the passenger seat all the way forward to accommodate extra leg room. She helped Joseph stand up from the wheelchair and he insisted on easing himself into his booster seat in the back. Mom placed his new crutches in after. The older nurse said her goodbye, taking the wheelchair with her. A call came in while they were part way home. “Your Grandma,” she muttered, slipping in one earbud connected to her phone. Joseph listened in but pretended to focus on the landscape of suburban homes passing by. Mom was good at whispering, but he did pick up small phrases between her and Grandma. “It’s called plasmacytomas. They said it’s genetic, but I’ve never heard of it. Come clean, Dianne. If you know something about this, say it.” Her eyes would occasionally meet his glances in the rear-view mirror, despite his best efforts to not let that happen. He was aware of the word ‘genetic’ but couldn’t remember from where. She got louder. “I knew he was seeing a doctor, but for arthritis… yes, yes, he told me arthritis… Well, don’t you think I should’ve known this earlier?” Mom listened to a response, but only briefly. “Doctor, patient confidentiality… you weren’t the patient, Dianne!” Joseph itched his shin just above where the cast ended and became lost in thought. Amongst a sea of disparate images swirling in his mind, he swore he could see his father’s red sports car whiz by them. Plasmacytomas. How do you spell that? It had been a day since coming home from the hospital and Joseph was hiding away in his bedroom all morning. The crutches were tiring to use so he asked to borrow the family laptop in bed. Instead of watching his usual YouTube channels, Joseph sat back against his pillows and made use of Google to look up this strange word he had heard the other day. Much of his time went to simply finding the proper type of cancer that he had, rather than accidently replacing it with the other complicated words he came across. Occasionally, Mom would pace by his bedroom door. When she brought him a sandwich for lunch, he minimized the current website he was on. She didn’t stay though, allowing him to continue reading. From what he could understand, it was a type of bone cancer. Images showed cross-sections of infected areas looking like honeycombs. That’s why his ankle was so brittle. When the sun set, Mom helped him through a very difficult bathing experience before he was able to slide into bed. Their only discussion throughout was how to navigate the swim trunks over his cast, and where any remaining soap suds were hiding. While laying in bed, he thought of some questions. Three came to mind. He mentally repeated them to not forget. What happens next? Will I ever be the same again? Am I going to die? He wasn’t ready to ask them, not yet. “Just be a boy,” Mom had told him so many times before. Answers to those questions were more than he felt a boy should know. So, they were put in that same mental corner as Santa Clause, the Tooth Fairy, and news of his father’s death. Dad. Is this how it starts? Is this how the machine gets me? He focused on the impending visit that he was sure to have that night. The Whirling Bone Machine. Returning to take him. Sleep came, even with the discomfort and pain of his cast. A dream began. He found himself in an attic, though it didn’t resemble theirs. A dead pixie-looking creature lay ahead. It was much larger than him, with teeth scattered on the plywood floor. To the left of the carcass was a big man in a Santa outfit, face-down and not moving. To the right, another person similarly lifeless. It was Dad. Those light jeans, combat boots, and tan jacket. While his facial features were too dimly lit, Joseph knew. The sound of chains dragged along the floor behind him. He spun to see the horrifying machine looming once more, spinning slowly. The figures that rode it wasted no time leaping down, tackling Joseph to the ground with force. Four of them this time, all grabbing a limb and pulling. His right ankle gave way first, tossing a figure backwards with Joseph’s foot in hand. The other continued, making him feel like he was about to tear apart completely, like his rotisserie chicken from days before. “Please, wake up!” Joseph shouted. It was no use, this was it. Death. But, moments later, his eyes darted open to the familiar stippled ceiling above his bed. Still alive for the time being, covered in sweat. Joseph returned to school two days later, teachers assisted him with every move. The crutches were still difficult to navigate. Mom had informed the adults of his diagnosis but, to other students, Joseph insisted they believe it was just an ankle break. “Clumsy Joey! Oh, that’s going to stick,” Hunter, the class bully, sneered. Joseph humoured him and continued smiling as other classmates joined in, showing equal part sympathy and teasing. Throughout the day, his responses were little more than a simple, “yes,” or “no.” Some kids even had broken bone stories of their own, and they’d explain the worst was getting the cast on. One girl even told him that healing was easy, just keep his weight off it and don’t get the cast wet. Healing won’t be easy for me. His cast grew heavier throughout the day. Those who had picked up on his downbeat behaviour seemed to distance themselves after lunch. During math, Joseph’s eyelids drooped from such a poor night’s sleep. When his mother picked him up, he shuffled into the car and closed the door himself. She had her sunglasses on, despite the overcast weather, and was sipping from a large coffee cup. He figured she was also losing rest. Joseph buckled in and his first of the three questions slipped from his mouth. “What comes next?” It surprised him, like a hiccup would. “That’s quite the greeting, Joey. Well, we’ve got some veggies I’m going to grill for dinner. Your show is on tonight—” “No. With the cancer.” Mom winced, as if she had just heard him curse. “Well, I’ve been talking to Doctor Marley’s office. The man we met at the hospital. There’ll be lots of tests and treatments to start removing it from your body. Chemotherapy.” “Chemotherapy.” Joseph bowed his head. “Mom, can I ask you something else?” “Okay…” “You told Grandma it was genetic. Did Dad have cancer? Is that why he left?” He felt her use the gas and brake pedal just a little firmer. “Your father was an idiot. Why he left doesn’t matter. The fact that he left though, Joey, that’s what matters. Sick or not, you don’t abandon family.” “Yeah, but Mom. Maybe he had a reason for leaving. Like, he didn’t want to hurt you and just wanted to get better by himself.” “No,” she whispered. He pressed on. “Maybe he knew it would hurt us both if he stayed. Not just with feelings, but maybe we’d get sick too. And Dad was just—" “Seriously, fuck him! Nobody’s doing me any favours by running away. No, Joey, he was a bad man who abandoned his family. This whole stupid mess is his fault! It’s his blood flowing through you that’s causing you to be sick. Still, you feel the need to sympathise with him. Just, just stop it. No more talk of the man who destroyed our lives.” There was a long pause. “Sorry for swearing.” “That’s… you swear sometimes. That’s okay, Dad did too. Didn’t he?” “No, Joey.” She lifted her sunglasses to rub both eyes, leaving no hand on the steering wheel momentarily. “No more talk.” Despite feeling the urge to continue defending a man he barely knew from the one person he loved more than anyone else in the world, Joseph fell quiet. If I make her too mad, I’ll be alone. That’s when the bone machine will come. Joseph remained silent for the remainder of the drive. Once home, he barely ate, and went to bed before his favourite show aired. Day two of chemotherapy was worse than day one. The bag of mixed fluids being pumped into him at the hospital was making Joseph feel woozy. Just before arriving, he threw up in the front yard. No blood, a nurse asked him to keep an eye out for that, just most of his breakfast. Other kids were there as well in the other recliner chairs. Maybe a dozen. Some normal looking while others were much worse. White, see-through, tired. Dying. His mother returned to the side of his recliner chair with a smoothie. He took reluctant swigs while watching the built-in monitor ahead. The headphones and cartoons helped drown out the commotion from the other half-dozen patients and their family. One girl across the room from him coughed and spasmed, which caught his eye. Each cough came quicker than the last, then she was honking, like geese do while chasing pieces of bread at the pond. Her father rubbed the young girl’s back while she continued without a breath. A nurse came to their aid. The coughs and gags turned to screaming. “No more! No, Daddy! no more, please!” Her father asked the nurse could disconnect his daughter’s tube. “Not until the treatment is complete, I’m afraid.” This commotion continued as Joseph popped each earbud out. He turned to his mother and asked the second question. “Will I ever be normal again?” She glanced up from her phone. He could feel her reading him, trying to understand. One of her hands met the top of his, the IV needle between them. “We won’t stop fighting until you are. I know you will pull through.” “But the doctor said more areas, not just my ankle. It’s spreading. Multiple something…” “Multiple myeloma. Yes, but real early.” Joseph’s third question, the one he wanted to ask the most, nearly tumbled out of his mouth right then and there. Fear held it in. Fear of the answer. Instead, he said, “I wish I were better already. I don’t like seeing you so sad.” She winced and looked away. He hadn’t meant to make her cry. Maybe, he thought, she was extra sensitive today. After all, Joseph figured she also noticed what he already observed when first entering this room. All other patients had their dads present. Joseph didn’t ask his last question until two weeks later. Him and Mom were in Doctor Marley’s office for a debrief between rounds of chemotherapy. Even free of the treatment for several weeks, there was hardly a day that didn’t have some follow-up or discussion regarding his sickness. Joseph found one aspect of the treatments comforting – he was too ill for dreams. They were nonexistent during the miserable month-long cycle. It was only over the past few nights was he lucid again to notice the Whirling Bone Machine was still there. Lurking in the shadows, readying to approach him once more. This meeting was about his ankle. The doctor had Joseph sit atop an examination table while viewing X-rays. His cancer had made healing impossible. Instead, he needed a new ankle. One made of metal and plastic. “You’ll be like Iron Man, Joseph. Do you like Iron Man?” “Not really,” he said. Joseph knew Iron Man’s suit was on the outside, not inside his body. “Maybe, more like Wolverine.” Since treatments began, he had become considerably less hairy than the clawed superhero. And weaker, too. Doctor Marley chuckled. “The imagination on you, Joseph! Isn’t that right, Mom?” His mother twirled her hair while listening along but remained mute. Joseph worried she’d twirl it until the strands snapped. “I know this is a bit of a shock,” the doctor corrected himself back to a more serious tone. He gestured with his hands in the white coat. “Mary will provide you with a surgery date on your way out, which will be in the coming days. Do either of you have any questions at this point?” Mom looked glazed over. Defeated? He was hit with a sense of panic usually reserved only for his nightmares. His third question found space to escape between these thoughts. “Am I going to die?” The doctor brought his chair closer to the examination table and leaned in. “Ah, oh, Joseph.” He drew in a breath before continuing. “Ankle surgery is very routine for us professionals. We perform this often, usually with older patients who can’t even heal as quickly as you young bucks. What you just asked shouldn’t even be on—” “Doc.” Mom had straightened herself up. “Please give us a minute alone.” That tone. Joseph wondered if he was in trouble. Doctor Marley must have picked up on it as well, giving them both a nod and closing the door behind him. “Why did you ask that, Joey?” He stumbled to provide an answer at first. Words did come, mixed with a whimper. “This is only getting worse. Mom, I’m not strong enough.” Tears came to Joseph’s eyes, and he started weeping. She scooped him up, holding his boney frame close. “You’re strong,” she said. “Tougher than this sickness.” “Dad wasn’t.” Joseph felt her freeze. “Wait,” she said. “What do you mean by that?” “No, nothing! I, I… I’m not sure what I’m saying anymore.” Mom pressed on, talking into his ear while not letting go. “What have you put together about him?” “Put together?” “Yeah, you said he wasn’t. Wasn’t what?” “I think… no. I know he’s dead.” She sat up straight, looking at him with her mouth agape. “You know!” “Yes, Mom. Last Easter, you and Auntie Sue and Uncle John said it.” She sat down in her chair. “You’re so smart, it’s what I’ve told everyone since you put that farmhouse puzzle back together at one years old. Yet even I underestimate you still. Not much of a child anymore, eh?” “No, I am! Promise.” Her eyes cast over him, scanning. “Do you miss him?” Joseph let out a sigh. “I don’t know.” “Joey. Dad… he was sick, but he also just gave up the fight one day.” “He did?” “I hid what happened from you out of spite towards that man. But I believe you’re so much stronger than he ever was. You have as much of me in you as him, and I don’t give up. Ever. Choose to live, Joey. Beat this thing.” “I want to beat this. I do. But…” “What?” “I think I’m really very sick.” Mom stood up and turned her back to Joseph for just a second. The air held something other than sanitizer in it. Thoughts. He could sense her cooking them up. She turned back. “Can you tell when I’m fibbing, Joey?” He hesitated before replying, “Like, lying? I think so.” “You know, your father was much more manipulative than I could ever hope to be. Still, for this time only, ignore the fact that I’m fibbing. Believe me as much as you believed Dad. Okay? As much as when he told you about this Whirling Bone Machine.” “Okay. Why?” “Well, because I’ve come to learn something about that infernal contraption. Something that will really surprise you.” She held his gaze, waiting for some type of signal from him. Had the fib begun already? Joseph bit his lower lip and twiddled his thumbs, then pressed ahead. “What did you find out?” “It only likes rotten bones. Sick bones. Don’t you see, Joey… it comes along to help. Like that knife-sharpening truck. You know, the one that fools all kids into thinking the ice cream man is on their street? It comes by to sharpen you up. Make you better.” He liked this game, even if she was fibbing. It always made Joseph laugh when she did uncomfortable things just for him, and this time was no different. “You’re forgetting about the spirits, Mom. The ones in robes that help run the machine.” “No, no, definitely didn’t! They’re the ones that come… what, put you in it, right?” She made a stuffing motion with her arms. He animated himself too, reaching into his shirt. “More like, pull my bones out to strap on the machine.” “Right!” She smirked. “That’s what I meant. They can smell the rotten bones!” The two of them kept their discussion going. It had become something like a competition, one attempting to up the other with details of the Whirling Bone Machine. They continued their conversation into the reception area, others looking at them with what Joseph assumed was a mix of annoyance and amusement. Though, he hardly minded while blabbering on about the machine to Mom, and she continued to reciprocate. Words just kept spilling out. The receptionist saw them off with a list of appointment dates, all while looking at them with an eyebrow raised. Before exiting the building, the two giggling family members stopped in at the pharmacy and bought two ice cream sandwiches. Mom helped Joseph out the front lobby doors so he could continue eating while using just one crutch. Joseph’s laughter made it difficult to steady himself. “Yes! That’s what I said! Really thick yarn holds it all together!” It was difficult to get the words out between gasps for air. “I would’ve never guessed!” Ice cream spilled from her mouth while talking. Some ran down her chin, which she attempted to catch it with her sleeve. He laughed and fell against a garbage can. She caught him before he slid to the ground. Once hoisted upright, he said, “I’m sorry for crying in the doctor’s office, Mom.” She ran a hand through his hair. “Oh, giving tears is okay, even giving bones is okay. If they’re rotten bones, Joey. Let’s give this bone machine of yours what it came for. Nothing more.” “Okay, but, even if it isn’t real?” “So, what if it isn’t real! Your dad made up the name, you created the image of this thing, and I’m saying how it can help to beat your cancer. Hell, that’s about the most cooperation this family has ever had.” “You’re right, Mom.” He adjusted his jacket and continued to lean on her, feeling comfort in knowing she wouldn’t let him fall. “I’ll feed it some bones. Only the rotten ones.” As they got to the car and took off back home, Joseph caught his reflection in the door window. A big smile. He also felt something that hadn’t been felt in a very long time. The desire for a sound sleep, and to dream again. That night, Joseph found himself back in the chemotherapy room. He seemed to be only inches tall, and the towering white recliner chairs all around were empty. Lights dimmed. The sound of chains dragging along laminate rang out from ahead. The Whirling Bone Machine slid under what little light remained above Joseph, casting a shadow on him. Its spin slowed and the riding figures glared. One growled, “you’re different today, Joey. You aren’t afraid.” “Correct,” he replied. “Why?” “Because, I have something for you.” Two figures dropped down to the ground and approached. They reached out so Joseph could lean on them, allowing him to hobble toward their contraption. Their cloaks smelled of dust, making him want to sneeze. With their boney hands, the two figures helped Joseph up onto the machine’s platform as it continued a slow rotation. “Welcome aboard,” one of them said as Joseph found himself a seat made of someone’s ribcage. The machine spooled up, gaining speed. Once moving at a fast pace, Joseph felt it shifting under him, moving away from the light. Casting him in darkness. Giving him comfort. Chris Preston is a writer of fiction and creative non-fiction from Ontario, Canada. Formal studies include University of Toronto’s Creative Writing program, as well as various workshops. You can currently see work by Chris within Mystery Weekly, Schlock! Webzine, JOURN-E and Hellbound Books. To find out more, feel free to visit www.seeprestonwrite.com. You may also follow Chris with the following twitter handle – @write_preston. Originally published July 5, 2022. |

AuthorLinda Gould hosts the Kaidankai, a weekly blog and podcast of fiction read out loud that explores the entire world of ghosts and the supernatural. The stories are touching, scary, gruesome, funny, and heartwarming. New episodes every Wednesday. |