|

“Muuhhhhhhhhh!” I always screamed – in my last days – so pathetically. I spent the last few years of my life that way – mooing like some sort of domesticated asshole. I knew the cow fields bordering Unpleasantville were dangerous – my mother had always made me well aware of that – but I couldn’t help running around out there. I had to get away from the smog – the muggy, toxic goop of that unnaturally shifting city. The relatively big sky allowed me to breathe; my chest contracted and retracted with pleasure, when I was there, as if at least relieved.

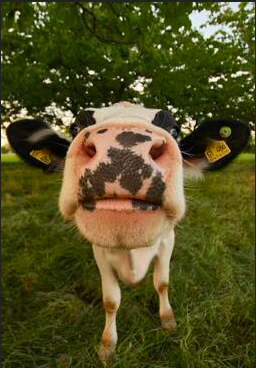

The cows always stared at me, as if watchful. I sprang through the fields, excited about a world primed for exploration. I sifted through the short, trampled grass, I climbed the fences, I trudged across the dirty creek – the cows, nearby, lapping up the muddy, swirling water.

I ran into Farmer Coleman only rarely. He wasn’t a very nice man – he just stared at me, as if he were planning something. I guess, retrospectively, I know that he was.

I tramped around the clumpy ground of the cow field, which was weathered by years of animal grazing. I stared up to the old red, cracked painted barn. I knew Farmer Coleman was always in there. He never spent any time in his actual house – which sat lonesome atop a nearby hill – he loved that barn. I laughed, cackling loudly into the free air, so fresh, so free away from the clutching smog of Unpleasantville.

On one occasion, I couldn’t stop. I continued belly laughing – wide-eyed and manic in my current state of joy. The cattle, disturbed, looked up to me. They glared at me, in both anger and fear, like Unpleasantville cattle – as everyone well knows – are prone to do. Their eyes widened, as if to shush me. They munched the grass in visibly apparent hatred, their mouths swirling in counter-clockwise fashion as the molars of their eerily human teeth ground up the brittle vegetation. They stared. Their eyes portrayed fear. I didn’t think much about that. I didn’t care about those cows.

Farmer Coleman sometimes noticed me jumping around. Most of the time, he was too lazy to do anything about it, but sometimes, he stormed out of the barn, through the field, yelling at me – trying to catch me. I’d just go home, when he did that, but I’d always come back the following day. Farmer Coleman hated me for that; he couldn’t snag me – he could only briefly shoo me away.

On overcast afternoon, I rolled around playfully in the field. The eternally purple Unpleasantville sky blended with the swirling grey clouds to create a fantastic, natural painting. I closed my eyes, nodding off to sleep. When I eventually opened them – heavy blinking and groggy – I saw standing atop me, staring — glaring, Farmer Coleman. He squinted at me, grinning. He grabbed me by the leg, dragging me through the bumpy field. I flailed about, but it was no use. He took me to the barn, dragging me even across the gravel of the road.

I knew the stories about the barn – about why the cows in the field were so bizarre. I didn’t believe any of those tales, but they didn’t seem terribly farfetched – especially considering the unnatural nature of Unpleasantville. The field, I determined, was at worst the safest place in the city – even if it was filled with previously human cattle; even if a psychotic, isolated landowner ran the place.

Farmer Coleman flipped open the wooden latch to the giant barn door and then swung it ajar. He threw me into the massive room, onto a hay-strewn, chalky dirt floor. I coughed. He chuckled nefariously:

“It’s time for an experiment,” he said, “It’s time to add to my cattle!”

He took me upstairs. He injected something into my neck. I passed out.

When I awoke, I was back out in the field. I stood erect, though on four legs instead of two. I mooed, and mooed again. I ate some grass; it was disgusting. It sat poorly in my stomach. I couldn’t stop eating it, though – it felt natural. It happened as if by instinct.

I lived the rest of my days as a cow, chewing cud, further grinding my withering, still human molars. Farmer Coleman hadn’t yet figured out the teeth, I guess.

I lived like that until the time came – the time in which I was led, by leash, from the field, back into the barn – for slaughter.

I’ve been gone for quite some time, now, but I can still see everything. I still exist – Unpleaantville refuses to release me from its toxic grip. I float around the swirling, haunted atmosphere of the place, absent – void, though still cognizant. Still here.

Farmer Coleman still adds to his herd, all the time. I can do nothing about that.

The cows moo.

Robert Pettus is an English as a Second Language teacher at the University of Cincinnati. Previously, he taught for four years in a combination of rural Thailand and Moscow, Russia. He was most recently accepted for publication at Tall Tale TV, Kaidankai, Black Petals, A Thin Line of Anxiety, Schlock, Inscape Literary Journal of Morehead State University, The Corner Bar Magazine,Yellow Mama, Apocalypse-Confidential, Mystery Tribune, Blood Moon Rising, and The Green Shoes Sanctuary.