|

The Ghost Runner by Vic Nogay  Photo by Briana Tozour on Unsplash Photo by Briana Tozour on Unsplash Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai Podcast. Veteran Monsters pitcher Mick McCullough thundered up the dugout steps to take the mound in the bottom of the 7th. Every muscle in his body was leaden, every joint rusty. It was a sweltering, tense Friday night—a home game for the Rockets with the Monsters in town—rivals clashing on the 4th of July. … You got this, Mick! … Stand tall, old man! … His coaches and teammates urged him on, but Mick was fading, and he knew it. All season he’d felt off, shaky, slowly coming undone. And tonight, pitch by pitch, his arm was giving out. Maybe he should have spoken up, passed the game off to the guys in the bullpen to finish it out, but at his age, he knew this was the last time, and he just wasn’t ready to say goodbye. He swallowed hard, the lurking death of his dream shrouding his focus. When he reached the mound, he circled it. Feigning nonchalance, he looked around the stadium, up into the stands, soaking it all in. The hot air sizzled as the sun went down. … be sure to stay after the game for the fireworks, folks … The announcer’s voice bounced around from the bleachers to the backstop—the reverberation, disorienting. Head foggy, arm throbbing, Mick toed the rubber as the Rockets rookie phenom Edgar Jimenez stepped up to the plate. Mick took the sign for low and away, wound up, and delivered, but the pitch sailed high and tight buzzing past Jimenez’s ear. He went down hard narrowly avoiding the ball, and he took his time rising from the dirt, stacking the crumbled pieces of himself back up like a building being demolished in reverse. He stared Mick down the whole time. Mick gave a halfhearted shrug and shook out his arm. Jimenez spat in Mick’s direction, adjusted his helmet, and walked it off. Mick stashed the ball in his glove and his glove under his arm, took his cap off his head and ran his fingers through his long hair, sweat greasing it into submission. The routine was meant to calm him, but his lungs sputtered, and his legs shook. Breathing deep, he looked up and saw his own haggard frame on the jumbotron in centerfield—his eyes caught the sharp edge of the sun peering through just beneath it. Sparks of light danced across his vision as he shook off the glare. Determined to recover, Mick settled in for the next pitch. But this time when the ball left his hand, he felt a pin stick deep in his shoulder, then pop and release. Wilting in pain, he grimaced and watched Jimenez absolutely crush it. The sound the bat made on the ball. was a ferocious boom no one could quite believe. Was it even possible for a wooden bat to be that loud? It was a massive bomb by the home team to tie the game. Cheers exploded from the seats. Then the boom came again. Unmistakable now, unobscured by the serendipitous crack of the bat the first time around. Mick startled and turned so he was staring where the ball had flown over the wall. That’s when the fireworks began to fly—the display meant for the end of the game—not up to the sky, but down towards the players on the field. A malfunction, a mistake, an attack, or a curse. The crowd ducked behind the seats, shrieking in fear. The players did the same, but on an open field, there was nowhere to hide. Some of them ran for the dugouts. The others lay prone in the grass, digging their fingers into the earth as if the crisply mowed blades of grass could save them. BOOM! BOOM! It seemed endless… but everything ends. When the explosions finally stopped, smoke had enveloped the park like a shroud. The final glinting beams from the red-orange sunset couldn’t burn it away as the sun would fog, so the smoke hung thick and yellow, bright, though no one could see a thing. Rain had been forecast for the late-night hours. Countercurrents of clean air cleared the way for the coming storm, slowly revealing the diamond’s horrors. The dugouts and stands stirred as the living rose to take in the scene. The outfield grass and infield dirt were dotted with remains like bugs drowned in the hot wax of a deep pillar candle. Jimenez had just rounded first, caught as if stealing. The Homeplate umpire had been blown upright against the backstop fence—crucified, as umpires often are. He was passing slowly between life and death, holding his watch like a sentinel over this sacred ground. After a moment of stillness, wraiths of the freshly dead surfaced above the bodies on the field, the air thickening into opacity. As they appeared, the game seemed briefly to pick up where it left off. The ghost of Jimenez celebrated as he crossed Homeplate, oblivious to the carnage around him. The ghost of Drew Potts in the on-deck circle lumbered confidently to the plate, nodding to the umpire up on the fence. And there was Mick in the center of it all. The body of the old pitcher lay dead in the dirt, but the ballplayer’s ghost lingered above the mound. Suddenly aware, the teammates and rivals regarded their spectral forms, then looked to the ground searching for their lifeless bodies. Upon finding themselves, one by one, the spirits began to slowly fade. The fresh air fish hooked itself into the tattered edges of their phantom frames and unspooled them, taking them away, bit by bit, to wherever it is ghosts go. Potts clutched his bat, incredulous, and assumed his batting stance. A frantic young Jimenez tried to sprint back on the field. And desperately, Mick held his glove up towards the plate, pleading for a brand-new ball. But no ball came, and the wind moved through. Vic Nogay (she/her) is a Pushcart Prize- and Best Microfiction-nominated poet and writer whose work appears in Fractured Lit, Barren Magazine, and Lost Balloon, among others. Her micro chapbook of poems, "under fire under water" was published in 2022 by tiny wren publishing. She is an Associate Poetry Editor for Identity Theory and lives in Columbus, Ohio. Find her online at vicnogay.com

0 Comments

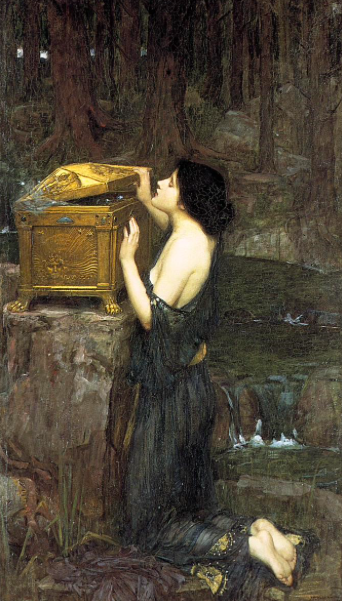

The Deal in Harlan’s Bar by David A. Cohen  Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai podcast. The woman wore too much makeup and bright red lipstick for Will’s taste. She sat next to the ballplayer uninvited and purred, “Hi there handsome, come to Harlan’s often?” in a voice that should have come from the lips of a much younger woman. Will figured her old enough to be his mother. She wasn’t his type, but he found it hard to say no. “Not now,” Will growled irritably. “Maybe later.” “Sure, hon. Maybe later.” The lady left the table as the bartender approached. “Whaddaya havin’?” “Whatever you got on tap, that’s strong.” “Ya don’t care?” “Just make it strong.” “I’ve a Belgian that will knock your socks off.” “Knock my socks off, then.” Will Marshall, recently traded to the New York Hudsons baseball team late in the 1958 season, had been a journeyman infielder known for his glove, not his bat. At 5’6” and 165 pounds of mostly muscle, he had character written on his weathered face, if not on his soul. Hardly anyone noticed his presence in the downtown bar despite the pennant fever sweeping through the city. He usually didn’t appear in a game until the seventh for defense and occasionally made a nice play that might matter. Will preferred drinking alone when playing at home. “Aren’t you that guy from the Hudsons?” The bartender finally recognized Marshall, though he couldn’t recall his name. “Yeah.” “This one and all the beer you can drink tonight on the house.” “That’s not a wise offer to make a ballplayer.” “I’ll take my chances,” the bartender smiled. Will sipped at his beer. He is, he thought, getting old for a ballplayer, thirty-two, and showing his age. He knew his days in the big leagues were nearing an end. No skills, not even a college degree, and not a day of actual work experience. His life had been all about baseball, mainly in the minors. “Maybe I could go out with a bang?” he thought. “Maybe you could,” came a voice to his left. A man in a gray jacket sporting an old fedora sitting on the barstool next to him had muttered the words. Will couldn’t get a good look at the stranger, the dark lighting and the fedora hiding most of his face. “I could what?” Will said, not understanding. “You could go out with a bang.” “What?” Will still couldn’t connect his thought and what the man had said. “Suppose you get to the Series, and because of some injuries, you get to start every day? Suppose you get to be a hero through the pennant drive and win the clincher to the Series in a walk-off?” Will laughed. “Yeah, and suppose pigs could fly.” “Maybe not pigs. Or maybe you can just end your career with a whimper.” “Who exactly are you?” “Mr. Weathers is the name.” The stranger held out his hand for a shake and quickly drew it back after not getting a response. “What are you, a sports writer?” Weathers grunted. “I perform magic.” “Where? In clubs? Vegas?” “Around.” “So, show me a trick.” “All right, I bet the bartender will come up to you and ask for your autograph for his kid in about another minute.” “How you gonna do that? Or do you just predict what’s going to happen?” “What difference does it make? Is it a bet?” “What are we betting?” “A gentlemen’s bet.” “Sure.” “Hey, Marshall,” the bartender approached, suddenly remembering the ballplayer’s name. “Can ya sign your autograph for my kid?” Will laughed and took a long drink from his beer. “Sure thing.” Mr. Weathers grunted again. “Let’s get a table, William.” “Look, Weathers, I’m not the brightest guy in the world, but I’m not stupid either. You set up this trick with the bartender and gave him a signal when to come over. What are you selling?” “You got me, Will. I’m selling the future. For you.” “What about my wife?” “We will get to that. Just suppose I know people. I could make some injuries happen where you play every day. Your big opportunity will come in the Yankees series.” “Great. Only one problem, I can’t hit worth a damn.” “Imagine you get pitches as you have never been getting before. Where you can hit them.” “You’re going to fix the pennant? What the hell is this, you the mob?” “No, not the mob. Let’s just say I know many people and can make things happen.” “So, you’re a gambler?” Will realized that he had been getting himself in deep just by talking to Weathers. The stranger laughed for the first time since coming into Will’s sight. “Yes, Will, I’m a big-time gambler.” “No, no, no, I don’t want to get drawn into anything like that. I can be banned just for talking to you. “ “This is an offer for your future. There is no danger of you being caught. I promise you that.” “Yeah, sure. Tell that to Shoeless Joe Jackson.” Weathers grunted. “Look, Will, I can make this happen to benefit both of us, and you will go on to have an exciting career. I promise you.” “You can make that happen? Damn. I didn’t know games were fixed like this.” “No, Will. It’s just for you.” “Why me?” “That’s my little secret, Will.” “You’ll make a bundle gambling?” “Yes, Will. I will be gambling with you.” “Christ. I’ve been wasting my time. I have no money to speak of, not for something like this. I’m leaving.” “Who said anything about money?” “Well, exactly what am I betting?” “You see, Will, you are betting me that you will make a deal I offer. If you take the deal, we both win the bet. Should you decline, we both lose.” “That makes no sense. How do you do this without gambling on the games?” “I’ll get something I want, Will. Your wife.” “What the hell? Are you crazy, man? You think I’m going to give you my wife? She belongs to me, you sick bastard. Get the hell away from me.” “This guy botherin’ you?” The bartender walked over when he heard the yelling. “Tell your friend, Mr. Weathers here, that he’s a sick bastard, and he should stay away from my wife!” With that, Will slammed his fist on the table, stood up, and walked out into the Manhattan night air. He lay on his bed, his wife at his side, and thought of Mr. Weathers. What a strange dude, he thought. Could he deliver? Could he, Will Marshall, become a superstar with big money, big press, and significant commercial contracts? Beth had been a good wife, but she wasn’t the only fish in the sea. What did Weathers mean that he “wanted” Beth? For a wife? For sex? For…? Beth belonged to him. He didn’t like the idea of another man taking away something he owned. Maybe he should get some guarantee of his success before agreeing to anything. Next off day, he’ll make a trip down to Harlan’s looking for Weathers. Next would be a home series with Cleveland, the Hudsons taking two of three. Will played in all three, pinch-hitting unsuccessfully in the first game and coming in for defensive purposes in the next two, which were wins. He went 1 for 4, raising his average above .200. The hit, a line drive to left-center, bounced over the fence for a ground-rule double. Fastball. He could hit the fastball. He had a lot more trouble with the breaking stuff. Occasionally a pitcher would forget that and think he could throw one by him when all he had to do was pitch a good slider, curve, or anything else that broke, and he would swing like a little girl at a pinata. Could Weathers get them to throw all fastballs, he wondered? The next break came on a Thursday, and Will headed for the bar where he had first met the odd man in the fedora. Will looked around but saw nothing. He sat at an empty table and waited. About an hour passed, and he was getting ready to leave when the unmistakable gray-jacketed man with the battered hat sat beside him. “Any change of heart, Will?” “Maybe. Two questions. What do you want Beth for, and how can I be sure you will uphold your end of the bargain?” “Second question first, Will. You have a great World Series, and then you divorce Beth in the offseason giving her half of all your assets now and half of your total income for five years from the date of the Series. That will pay for her attending medical school, something you have kept her from all these years. You will be getting plenty more. Our agreement ends at the end of the five years, and you are on your own with baseball. Should you not uphold your end of the deal, I am afraid your days as a major league superstar will be short-lived.” “Half,” Will exclaimed. “Hell, that’s a lot.” “Nonnegotiable, Will. Take it or leave it.” “What about Beth? What do you want with her? What do you mean I should give her to you?” “Divorce her, and I will take care of the rest. What I want her for is none of your business.” Will tapped his right hand nervously on the table. He didn’t like the idea of some other man getting his wife, something of his after all. This, though, was a once-in-a-lifetime deal, he thought. Then, with emphasis, he slammed his open hand down hard, shaking the two drinks the men had set on the tabletop, and he said as he extended his hand, “Deal.” Weathers smiled – Will could barely see a crack of the lips under the shade of that hat – and held out his hand, grasping Will’s, shaking it vigorously up and down almost violently. “Deal,” Weathers replied. Will thought Weathers’ hand felt odd, even painful, cold to the touch, like ice applied to a burning wound. A strange thought occurred to Will. He had heard stories about the Devil making deals for people’s souls. He knew he would sound dumb, but he asked anyway. “You’re not the Devil or a Demon, are you.” Weathers laughed. “No, Will. I promise you I am neither of those. Nothing like that at all. Just a man who cares about your wife, that’s all.” The Hudsons tied for first with three games left to play against the Yankees for the pennant. Will, entered the first game in the sixth and hit a changeup for a home run. In his next at-bat, batting from the left, he caught a slider for a double down the left-field line driving in the tying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth. The following two games found Will starting for the first time with the Hudsons, and he again consistently delivered, making several outstanding defensive plays. Will was thrilled at the idea that he had become a crowd favorite for the first time in his career. The Hudsons demolished the Yankees in three straight with a barrage of hits against their vaunted pitching staff. Will hadn’t mentioned anything to Beth about his plans to divorce her. He concentrated on the games. The World Series transformed New York into a city of magic, excitement brimming in the unlikeliest places. People who never watched baseball or any sport wore merchandise for their team. The mayor made pronouncements and issued proclamations; the governor made a bet with the governor of Wisconsin over his beloved Milwaukee Braves, the opponent of the Hudsons in the Series. Beth sat in a special section for the wives. She rooted for the Hudsons throughout the season, whether or not Will played. Now that Will displayed a hot bat and glove, he started Game One, promptly delivering four hits, including a home run. He did everything, flashing his glove in defensive gems, swooping up the ball with the skill of a veteran superstar, making throws of strength and accuracy, and even stealing a base, something he never thought he could do in a game. Each of the next six games proved him to be a man of unmatched skills, extraordinarily transformed from a hack who never before gave a clue of any unique talent into a star. No one was startled or more ecstatic than Will by this luck. Game Seven proved his greatest success—many a boy and not a few girls dream of this moment. Bases loaded, two out, the winning run at the plate, and Will coming to bat. He watched five pitches go by, two for strikes and three for balls. Will hadn’t swung the bat yet. He guessed a slider for the next pitch. He looked into the box seats to find Beth. Instead, he noticed an odd man wearing a gray coat, an old fedora, and a bizarre grin. A chill went up and down his spine. He gripped the bat tighter. He could feel the sweet part of the bat connect with the ball, hanging over the plate, hitting it into the upper deck of center field—an enormous blast, winning the series on a grand slam. The home crowd adored him, and the television commentators loved the drama of the live TV moment. Will, offered the opportunity, negotiated a new contract with a significant increase in salary and bonuses. Commercial offers soon poured in, and Marshall appeared on the Ed Sullivan and the late-night Jack Paar show with the requisite jokes and pandering praise for his newfound skills. Will now went to the famous sports pubs of his baseball friends and drank with his best buddies. Women followed more easily, and now he found them easier to conquer. “Weathers, I knew you’d show up.” Marshall excused himself from his companions, explaining Weathers as a distant relative who had come to see him on some family matter. “I have come to collect, Will.” “Okay, okay, no problem. I will tell Beth this evening.” “You will give her half of all your assets and half of your future earnings over the next five years as you agreed?” “Yeah, sure. If I keep playing like this, I will honor my side of the deal. That night dining alone with Beth, Will broke the news to his wife. “Beth, listen. I don’t want to hurt you, Babe, but I’ve been having an affair with another woman.” Beth smiled. “I know, Will, lots of women, you mean.” “Yeah, well, that too. But this one is special, Beth. I intend to get us a divorce.” Beth’s smile turned into a grimace of shock and pain. “You bastard. You make it now, and now is the time you want to divorce me?” “No, no, Babe, you got me wrong. I intend to do well by you.” “Don’t call me Babe, you piece of shit. Get out of here now before I kill you.” “Sure, sure, I understand. Just want to let you know I am giving you half of everything now and for the next five years. How about that?” “GET OUT!” “I’ll pay all of the taxes, I swear!” “Get the hell out, or I’ll throw you out.” Beth took an empty plate that had held her dinner and threw it at Will’s head. She missed. Will grabbed a bag he had already packed and told Beth he would return for the rest. “Ungrateful bitch,” he whispered under his breath. The years went by with the name of Will Marshall uttered in the same breath as Mantle, Mays, and Robinson. He lacked for nothing: fame, women, and money. Five years had passed, and his agreement with Weathers had reached its expiration date. Now thirty-seven, he decided to retire rather than risk failure. Will decided, upon retirement, to sell his place and relocate to Florida. He prepared for the move by going through his belongings. He found a box of some random items of Beth’s that she had inadvertently left behind. There, flattened under several music albums, he saw an old, worn fedora. It must have been from someone Beth knew, he thought. Holding it in his hand, he considered how much the fedora looked like Weathers’ hat. Will, on an impulse, decided to call Beth after years of only communicating through lawyers. Maybe she is lonely, he thought. Beth, at first reluctant to visit Will, decided to go to retrieve the box her ex had discovered. She brought along some mace, not knowing what to expect. Will answered the door and invited Beth in with a civil, “Hi Beth.” She provided half a smile, which was about all she could manage. “Let me take that for you.” Will, attempting to behave like a gentleman, indicated Beth’s coat. “No. I won’t be staying long. Where’s the box?” “Let me carry them out for you.” Beth surprised that Will did not make a move on her, gave a curt, “Thank you.” Will lifted the box and carried it toward the door. He paused. A sharp pain passed through his right arm. His chest felt like a truck had landed on it, and he suddenly found breathing difficult. The box fell to the floor, and he followed. “Help me, Beth.” “Dammit, Will. I’ve only just begun med school.” She rushed to the phone and dialed the Operator, calling for an ambulance. Dropping to her knees, she began chest compressions. Will heard the sultry voice of Peggy Lee singing a song in the background. He stared at Beth and blinked several times. Her face blurred and then returned into sharp focus. Only now, he saw a man, appearing translucent and wearing a gray jacket and an old fedora atop his head, standing behind the woman he had abused for years, who now fought hard to save his life. Beth’s dad smiled and placed his hands lovingly on his daughter’s shoulders as Will drew his last breath. David is a retired reference librarian who started writing fiction three years ago. He has an MA in Political Science and an MLS in librarianship. The Deal in Harlan's Bar is his seventh story to be published. His other recent story - Where Have All the Young Girls Gone? - appears in After Dinner Conversation - Best of 2022. Besides writing, David enjoys classical music and, of course, Baseball. Born and raised in New York he is a NY Mets fan. He now lives near Philadelphia with his wife and cat, Muppet. Pandora Boxed by Matthew McAyeal "Pandora Boxed" is adapted from Greek mythology. It was previously published by "Bards and Sages Quarterly," "Scarlet Leaf Review," "Tall Tale TV," "DM du Jour," "The Magazine of History & Fiction," "Short Kid Stories," and "cc&d".  Pandora by John William Waterhouse, 1896 Pandora by John William Waterhouse, 1896 Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai Podcast. Pandora couldn’t sleep. She kept thinking about that box she wasn’t supposed to open. And was it past midnight by now? If not, it was still her first day of existence. She thought back to how her day, indeed her life, had started. Up on Mount Olympus, Zeus had ordered Hephaestus to create Pandora from water and earth. As soon as she was formed, the other gods started giving her gifts. Aphrodite gave her beauty, Hermes gave her the ability to talk, and Athena gave her fine clothes to wear. She was also given necklaces, jewelry, and a tiara. At this point, Pandora was feeling really good about herself. It was only her first day of existing, after all. She must be really special for the gods to be giving her so many wonderful gifts! After all the other gods had given her a gift, Zeus himself stepped forward. He handed her a magnificent box and told her not to open it. “Why not?” she asked. Being so new, Pandora’s mind up to now had felt like it wasn’t fully formed. It was a sensation, like being only half-awake. That moment, when she questioned something for the first time, might have been when she finally started to develop real, concrete thoughts. “Because I have ordered it,” said Zeus. “But why?” Pandora persisted. This didn’t make any sense to her. “I am the king of the gods and you will obey me,” said Zeus. “You are also to go down to earth and marry a man named Epimetheus.” “What does ‘marry’ mean?” asked Pandora. “Marriage is a beautiful thing,” said Hera. “It means you devote yourself to someone else and you two become partners in life.” “But I don’t even know this Epimetheus!” Pandora objected. “How can I marry him?” “You were created to give him companionship,” Zeus explained. And so, Pandora walked down from Mount Olympus, carrying the box which she wasn’t allowed to open. She had only just been created and already she had a lot to think about. If her purpose in life was to give companionship to Epimetheus, she supposed she ought to do it. But why were thoughts counter to that swimming around in her mind? She found herself thinking that maybe she didn’t want to marry Epimetheus, that her being ordered to do so wasn’t fair. If giving companionship to Epimetheus was the purpose for which she was created, why had she been given the ability to think these thoughts? It didn’t make sense. And what was in the box? Why wasn’t she allowed to open it? If Zeus said not to open it, he must have had a good reason, but why wouldn’t he share the reason with her? Why was the box given to her if she wasn’t allowed to open it? Would she be allowed to open it when she got to Epimetheus? She hoped so. She was really curious about it. She kept wanting to take just one little peek inside, but resisted it. She told herself that if she was supposed to open it later, she would feel really bad about opening it now. She could be patient. She could be good. But why had she been given the ability to think of doing otherwise? Could she actually do otherwise? Pandora stopped walking, suddenly overcome by doubt. Who was she? Well, that seemed pretty straightforward. She was Pandora. She was created by the gods. She was to be the wife of Epimetheus. She was the person carrying the box she wasn’t allowed to open. This was her whole identity, literally everything she knew about herself. If she deviated from that, she would know nothing, almost be nothing, but the only identity she did have was full of questions and contradictions. It was so scary. Who was she? Who was she, really? Pandora shook herself and continued on down the mountain, still not opening the box. Finally, she got to Epimetheus. She hoped he would have some answers. She had decided that she would do what she was supposed to. She would marry Epimetheus. She would give him love and companionship. She would be good. “Hello,” she said to him, trying to smile pleasantly. “I’m Pandora.” Suddenly, her hands, still holding the box, started to shake. She felt really nervous! “Zeus sent you here, didn’t he?” asked Epimetheus. “Yes!” Pandora exclaimed and she ran forward. Finally, her questions would be answered! “Do you know what’s in the box? Zeus told me not to open it.” She handed the box to him. “I don’t know,” said Epimetheus, “but I know I wouldn’t open it.” Pandora’s hopes crashed, but she felt glad that at least the box wasn’t only her problem now. “I’m supposed to marry you,” she explained eagerly. “Of course you are,” Epimetheus replied rather cynically. Pandora felt like her heart was being crushed. Marrying Epimetheus was supposed to be her purpose in life! If he didn’t want her, what meaning did her life have? Who was she if not Epimetheus’s wife? “I… I d-don’t understand,” she said, her voice shaking. “Let me explain it to you,” said Epimetheus. “I helped my brother Prometheus steal fire from the gods and give it to humans. Zeus was very angry and punished him by chaining him to a rock. And now he’s sent you down here to punish me.” “I don’t want to punish you!” exclaimed Pandora at once. “Well, that’s what you were created for,” said Epimetheus. Pandora didn’t know what to think. She had only existed for a few hours and already she was being told that her entire identity was a lie! What was she to believe? What was she to do? Who was she? If she was just a tool for delivering punishment, why could she think? Why could she feel? Why did she want to be good? Why could she ask who she was? Finally, she decided to tell Epimetheus the truth. “I don’t know why the gods created me,” she said. “They told me I was supposed to give you companionship. I don’t know if that’s true, but I’ll be your wife if you’ll take me.” “I believe you are sincere,” Epimetheus replied. “I will marry you.” They were married that afternoon, but Pandora continued thinking. The gods had told her to marry Epimetheus and had not explicitly told her to punish him, so she could be a good wife to him without being in defiance of the gods. She had decided that that was what she would do for now. If both Epimetheus and the gods agreed on something, she supposed she ought to do it. But would the gods come along later and tell her to punish him? If they did, what would she do? Would she defy the gods? Whose side was she on? Being new to the world, Pandora felt she had no way of knowing who was right and who was wrong. Punishing Epimetheus felt wrong to her, but maybe it was right if that’s what the gods wanted. Or was Epimetheus wrong about her being there to punish him? Maybe he was just paranoid. If he was paranoid, why would he think that and why would Zeus want to give a wife to such a person? As she lay in bed that night, Pandora was still thinking about these things. It was really quite a cruel thing to create a being for the purpose of delivering a punishment and then give that being the ability to think and feel and question. She thought of how confused she had thought she was when she had been walking down Mount Olympus. That now felt like a long-ago age of innocence, a time when her life had a clear purpose. And what was in the stupid box? She had spent the first hours of her life carrying that box all the way down from Mount Olympus. She felt like the box was almost part of her, and now it was clear that she would never find out what was actually in it. It wasn’t fair! But Epimetheus and the gods had both told her that she should not open the box, so she supposed that she shouldn’t. Pandora sat up. Her life made no sense! Since she had been created, she had had a million questions and nothing had been explained to her satisfaction. She was mad. Why had the gods made her like this? She could dimly recall the beginning of her life when she had thought that she must be very special, but she sure didn’t feel special now. She still had all that gold and jewelry, but now it meant nothing. She didn’t want pretty clothes and jewelry. She wanted answers! She got up, walked across the room, and picked up the box. What was inside the box? Did it contain the answers? It would at least contain the answer to the question of what was inside the box. Why shouldn’t she open it? Because the gods told her not to? Why should she listen to them? They hadn’t treated her right. They had given her a life full of questions and explained nothing. She felt more confused than ever about who she was and what the purpose of her life was supposed to be. They should have explained those things to her, but they hadn’t. If they weren’t going to explain anything, then she was going to find out on her own! That would show them! Pandora opened the box and all the evils to plague humanity were released, just as Zeus had planned from the beginning. Matthew McAyeal is a writer from Portland, Oregon. His short stories have been published by "Bards and Sages Quarterly," "Fantasia Divinity Magazine," "cc&d," "The Fear of Monkeys," "Danse Macabre," "Scarlet Leaf Magazine," "Bewildering Stories," "Tall Tale TV," "Fiction on the Web," "Quail Bell Magazine," "MetaStellar," and "Kaidankai." In 2008, two screenplays he wrote were semi-finalists in the Screenplay Festival. The House of Many Rooms by Geoffrey Marshall  Photo by Dima Pechurin on Unsplash Photo by Dima Pechurin on Unsplash Click here to listen to this story on the Kaidankai Podcast. Mantegna the Psychic dropped the phone. He fumbled blindly until his fingers brushed the smooth glass, but that nudged the buzzing device deeper beneath the car seat. Goddamn thing — he took his eyes off the road and made a grab. All he could think of was a caveman lunging for a trout but at least he did manage to snag the corner. He pulled it into the clear beside his feet and triumphantly seized the device. At least the screen seemed ok. Lucky for him since he couldn’t afford to replace a cracked screen. He was on his last dime and living on faith and instant ramen bowls was no fun. None whatsoever. At last he nudged the device into the clear beside his feet and picked it up. Returing to his unknown caller who had been on the phone when he dropped it, he said, “Hello,” he said, “did you say your were a lawyer?” She had. “Sorry, just dropped my phone, I had to make a turn,” he said. There was a disapproving silence from the lawyer. “I’m not driving,” he blurted. “I pulled over,” he lied. His hands tightened on the wheel. Not everyone can afford flashy German cars with their fancy handsfree phones. Didn’t she know that? If she sensed his angst, she ignored it. If Mantegna was available he should come to her office. He had received an inheritance from her client.That got his attention — after all, why would a lawyer call him? he had wondered. Was he being sued? Then again, the venues that hired him paid so little that a small claims summons was more likely. He quickly agreed to go to her office. He knew the place, nestled as it was along the two coffee shops on the main drag — the first, Starbucks, was usually jammed with clientele, and the other, a mostly deserted independent, he supposed perpetually tottering on the verge of bankruptcy. He could sympathize. He hung up and continued driving, just this little bit happier that he was before. Seeing that ‘Unknown Number’ had made the hair stand up on the back of his neck but he felt better now. He flipped on the radio. There was only static so he turned the knob until he found some music and started bopping along — and as he bopped his recalled the last call he received from Unknown Number. He was asleep or at least on the cusp. He felt something creepy crawling along his finger — something small. The tickle had jumpstarted the slow process of waking him up but the sting of two small bites jolted him awake. He reflexively pinched his thumb down and felt a gooey mash. His finger started to itch. What the hell? He turned on his night light to examine his finger. Whatever had bit him was now squished beyond recognition. An itchy red lump was swelling up. Maybe he had some cream in the bathroom. He rolled over and planted his feet on the floor with a smack, just as his phone buzzed on the nightstand — Unknown Caller. Who called in the middle of the goddamn night? He stabbed his finger at the green button. “Hello?” “Mr. Mantegna?” a faint, faraway voice — crackling static interfered with the connection, “The Psychic?” He attempted to sound cheerful even as a quick glance at the digits on his clock made him wince. Two thirty. Damn. The witching hour. “Can I help you?” He listened calmly as she explained her situation. He brother long passed. Tragic accident. She needed closure after all those years. Perhaps he could — after all, he was a true psychic — perhaps he could help her. A séance. She was sure he could do it. She had heard he was a real psychic. She was sure he could do it. “Look — lady — ma’am,”, he mumbled with sleep-slurred speech, “Could you just call in the morning?” “Can you do it?” she whispered, static rising and falling like waves on a beach. “Of course, just call back in the —” She didn’t wait for him to finish and instead rattled off a time, date and address in rapid succession. He had no chance to get a word in edgewise so he set the phone down and scrambled for a pen. “Mr. Mantegna,” she asked after waiting a few moments, “are you still there?” “I’m here, I’m here,” he shouted into the phone. No reply. He checked the display — the call was disconnected. What the hell? After giving him all that info? Not knowing what else to do, he flipped the lights back out and crashed back to bed. Maybe this as all just a bad dream. Sleep wouldn’t come — his finger throbbed and his mind was worried. He tossed and turned for hours before the sweetness sleep finally came. The next morning, he was surprised to find the bite gone as if it never happened — or maybe it really was just a dream? He found the scribbled note with the lady’s information. At least that happened. He balled up the note but stopped himself from tossing it in the wastebasket. She was a paying customer after all. He smoothed out the paper and stuck it behind a fridge magnet and promptly forgot the entire incident. Over the next couple of weeks he would notice the note every so ofter. Was it legit? Did he dream the whole thing and just write some nonsense down? Should he go? He didn’t even get a deposit. She had agreed to his usual fee though. He felt sure he had brought that up. When the date at last approached he was short for rent which helped firm his resolve. He waited until the appointed hour approached and suited up — black pants and shoes, a white shirt, and, of course, how could he go out without his cape? The one with the red lining. Just the right dramatic flair for a psychic of his stature. He found himself sitting in his car as the last rays of sunlight trickled away and twilight gave way to night — still waffling. To go or not to go? He punched the address into his GPS and waited — and waited. No results. He tried his phone. Same thing. Other services. Identical. We’re sorry, the specified address could not be found. He tried again, only using the street name. He breathed a sigh of relief when it popped up so he keyed in a house number one down. It worked — well, at least that was something. He would get as close as he could, then walk along the street until he found the house — and he did. He shuddered when he saw the place. So creepy. Creepy houses come in all sizes and shapes. Mantegna had seen his fair share — from drab suburban bungalows, windows opaque from nicotine with a hornet’s nest seething under the mailbox to dilapidated Psycho mansions. The very worst of the worst had a feeling on common — a malignant presence. The first thing you will notice when you come up a house such as this is that you will feel as if the house is watching you — and this house, Number Seven Edgar Lane, had that same feeling. Haunted. Had to be. At first glance, the house was beautiful — with brightly painted wooden shingles, white as snow like rows of perfect teeth. The roof, clad with perfectly squared new-looking roof shingles. The shutters, a dark green, sashed like droopy eyelids. The carefully tended flower garden, enormous globular roses hanging, ready to drop on the freshly mowed lawn. Sprinklers going. Bees buzzing. Windows shining. Yet this was merely veneer and beneath the superficial prettiness Mantegna sensed a darker undercurrent. The buzzing of bees could be the murmur of fevered whispers. Look away for even a second, and a lonely silhouette might peek from behind a curtain — an imprint of shadow in the corner of your retina. Mantegna felt the house watch him all too closely as he made his was up the painted concrete stones of the walkway. He was about to knock when the door opened. “Mr. Mantegna?” “Why, yes, I —” he started to say when she interrupted him. She was beautiful (and far out of his league). He offered a small bow. “Madame, allow me to introduce myself,” he said in his stage voice. Yes, he was performing now. What the heck. It’s what she’s paying for after all. “You’re Mr. Mantegna, the famous psychic,” she said, “I’m Ginger —” “Let me guess,” Mantegna looked up from his bow, “Rogers?” “Why yes,” she seemed impressed. “While I do claim possess some meager psychic talents, madame,” he said, attempting in his New England way to channel a southern gentleman, “I must confess — it was my caller id.” She looked blank for a second or two, “As you say Mr. Mantegna.” She then offered a polite chuckle, “Although I do recall giving you my name during our conversation.” He felt like he was owed more than a chuckle (and a very slight chuckle at that) for his comedic effort. He straightened up from his bow as she stood aside. “Do come in,” she said, welcoming him into the haunted house at Seven Edgar Lane. The hallway that greeted him was scarcely lit. Where the exterior was as fresh and bright as a megawatt tv smile, the walls were lined with meagre and dust-shrouded bulbs perched on the sconces that proceeded down the dim hallway. The light was hesitant, as if fearful of what it might reveal should it reach into the deepest of the cobweb laced corners. A few photographs hung on the wall. They showed a family — two children, a girl and boy, posing with parents beaming at him across the decades, their joy all the more apparent for the flaws in the faded prints. “I live alone, ” she said. “These are all of my family,” she gestured at the photographs as she led him down the hall, “My father, mother, younger brother.” She fell silent. He noticed, somewhat ominously, that the row of photographs ended abruptly when the children looked about ten years old. Near the end of the hall, the walls were entirely bare, save for the intermittent sconces. Whoever designed this house, he figured, must have never heard of the whole “open concept” idea. The house seemed to consist of a maze of corridors periodically indented by the frames of closed doors. “No one else will be joining us,” she said turning a rattling doorknob, “I hope that’s not going to be a problem.” She gestured for him to enter. Ginger didn’t seem the type to need an audience. He shrugged, “All that matters is if the entity you wish to reach is willing.” The room was a dark and windowless box. Did they really build houses like this? Ginger flipped the light switch and a gigantic chandelier sputtered to life, diffusing an orangey light around the room. There was a large oval table beneath and eight chairs. Two cabinets, crammed with glassware and porcelain, stood against the wall. “Please take a seat Mr. Mantegna,” she offered a chair, “I confess, I have been trying to find someone such as yourself for an awfully long time.” Ok, not creepy, he thought while taking his seat. “Someone such as myself?” he asked. “A genuine psychic, of course,” she laughed and when she did her smile lit the room like bijou lights over a Broadway box office. His hands were flat on the table and he could feel the underlay beneath the satiny green tablecloth. This room was perfect for a séance he realized — as perfect as a movie set. They sat down opposite each other. “Tell me Ms. Rogers,” he said, “who would you like to contact?” She looked down at the table, “My brother,” she said. “His name was Freddy.” “The boy in the photographs?” “That’s right,” she replied, still staring at her hands. “There was a terrible accident when we were children and —” she had to pause as if to gather her thoughts. “When we were young — Mr. Mantegna, he died.” “I’m sorry for your loss,” he said, his voice as gentle as he could make it. “Thank you, but you see,” she looked up, “I just need to tell him that I’m sorry.” He nodded. “We need to join hands Ms. Rogers,” he said. “We’re making a circuit — a spiritual circuit.” As soon as their fingers touched, his vision flickered. Oh my god, he thought, there would be no need for tricks this time. This was a real as it got. The room flashed blue, as if someone was playing with a light switch and there was a humming in his ears that came and went with the strobe of blue light. After several moments of back and forth, the light steadied — so bright he could see dust motes hanging in the air. Ginger hadn’t moved. She sat as still as a statue. Everything seemed to be on pause — but he felt the need to stand. He broke contact with her hands — nothing changed. The room remained blue but there was no source for the light — or maybe it was more accurate to say that it emanated from the walls, the floors, the ceiling — even himself and Ginger. He stood up — and stepped outside of his body. He waved his hand in front of his own face — well, the face of the Mantegna that remained locked in a trance at the table. Well that’s pretty creepy. He was standing beside the table looking at Ginger and himself, still seated, facing each other, eyes locked and hands intertwined. He walked to the door. Somehow the doorknob responded to his touch. The same blue light illuminated the hallway, again, from no apparent source. He walked down a short ways towards the front of the house. As he passed the first doorway, he could hear voices. He opened the door a crack and peered inside. The light in the room was not blue, but warm and dim — produced by a bare oblong lightbulb sitting in a small lamp. The bulb contained several large filaments glowing orange and arranged around the central core. A girl was tucked under the covers in the lower bunk of a bunk bed. A man was sitting beside her and a boy was sitting cross-legged on top of the covers, arms locked around a teddy bear. “Give it back Freddy,” the little girl said. “That’s my brother.” Mantegna jumped, and even though he was apparently a disembodied spirit of some kind, at that moment he felt his heart lurch in his chest. Ginger was standing beside him now. When did she come in? he wondered as his pulse subsided. “And our father,” she continued. She was smiling — and crying. The children squabbled until Freddy was forced to hand over the bear which young Ginger immediately hid under the covers. Freddy climbed the ladder to the upper bunk. Their father selected a book and began to read as they slowly backed out of the room. Her father’s gentle drone continued as the door slowly swung shut of its own accord leaving Mantegna and Ginger once again in the blue lit hallway. “That room was not in this house,” she told him, “that was our first house. Freddy and I shared a room in those days.” They took a few more steps down the hall and a low murmur replaced her father’s voice — a murmur that slowly grew louder until the came to the next door, vibrating like a speaker cone from the tumult behind. He swung the door open to reveal a large room — impossibly large — even for a house the size of number 7 Edgar Lane. The room was crowded with people — diners — seated at rows of long wooden tables. The tables were stained a dark walnut and the floors and walls seemed to match, although the lighting was sporadic and failed to reach the distant corners. She leaned in, “My mother’s fortieth,” she said. There was a large bar at the far end of the room and a gleaming row of grills where chefs in formal uniforms sported tall white toques, double-breasted cloth jackets and long aprons toiled. Occasional jets of flame reached up and cast a warm, short-lived glow on the spotless outfits. Large industrial looking sheet-metal vents hovered just over the tops of the tottering toques. Guests seemed to be serving themselves, lining up cafeteria style for the cooks to serve. There were hundreds of guests. Ginger tugged on his sleeve, “People were crazy for cafeterias back then,” she indicated the lines, “they were everywhere.” Two children rushed past them, somehow avoiding them. Ginger and her brother, their appearance much the same as in the first room but looking a few years older. They dashed through the crowd towards two adults standing near the grills. Mantegna recognized the man as their father and the woman, who had a such a strong resemblance to Ginger, was clearly their mother. The grown ups hugged the children. One big happy family. He remembered his own family — father, cuffing in the back of his head. You’re gonna amount to beans, but I love you anyway, his old man had said. The room quieted to a hush, like someone pressed the mute button, and he heard a deep sob from his side — Ginger in the midst of a total breakdown. He patted her should, feeling awkward, doing it awkwardly — but he was pleasantly surprised to learn that they were solid enough, at least to each other. “There, there,” he mumbled, feeling like an idiot, “What is it? What happened?” She was just watching the younger version of herself and her brother in the embrace of their parents. He let his arm fall to his side and stood with her, observing the loving family. “This was the last day I saw my brother alive,” she said. “What is it you really want me here for?” he asked quietly. “I need to know.” “This is the day he died,” she said in a flat voice, still the loudest sound in the now muted room. “It was my fault —” she sucked in a deep breath, “I tried to save him but I just couldn’t reach him in time.” “How could it be your fault?” he asked, “You were only a child.” She didn’t answer except to turn away and slowly walk back towards the door. As she did, the sound rushed back like a rogue wave — the commotion of guests encumbered by tottering trays, children running and a hundred conversations swept back over them. Mantegna watched for a handful of seconds. When a tray appeared in his chest, loaded with fried chicken and a tiny dish of coleslaw he started to run after her leaving the staggering guest behind. Ginger was opening the door when he caught up and together crossed the threshold. Back in the hallway, the sounds of the party diminished and faded to silence as the door closed. Mantegna had a feeling that, if he opened the door again, it would be in a completely different place, and he might be lost in time like driftwood in a boundless sea. He didn’t know where it would open, just that it would be different. Who knows, maybe it would just be a plain old room. “Follow me and I will show you what happened,” Ginger beckoned. He kept himself glued to her side as she made her way to the door at the end of the hall. By rights this should open on the entrance to the street, where he first came in — but it did not, or at least not to the same street. They stepped through. Different, yet not altogether unfamiliar. Mantegna stood swiveling his head, like a periscope, up and down the street. Maybe it was the same street. Same street, different era. The passing cars had rounded fenders and tires with white sidewalls. Edgar Lane, not his Edgar Lane, but the street as it was fifty years ago. Young Ginger and Freddy opened the door and walked past them. They were squabbling, as they had in the first room, over a teddy bear. Freddy grabbed the bear and ran down the steps. Young Ginger gave chase. Beside him, her adult form gripped Mantegna’s hand. “You see,” she whispered through gritted teeth. Freddy stood on the curb, teasing the young Ginger and she yelled back, giving as good as she was getting. Give it back. Give it back. He laughed and she charged at him — he lurched into the road when they collided. Mantegna felt Ginger’s hand clamping on his wrist like a steel clamp. There came the sound of a horn. The screeching of tires. A car fishtailed towards Freddy who stood, paralyzed — immobilized by the shock of seeing the vehicle barreling his way. Young Ginger (and grown up Ginger simultaneously) called out his name. He turned to look. Her brother may have been frozen, but young Ginger was not. She hurled herself through the air at her brother. She tackled the boy as the car screeched sideways. Mantegna couldn’t see, the car had blocked his view. What happened? He turned to ask Ginger. She wasn’t there. Now the car, the street, the house — everything — all gone. Except for the door. He pulled at the handle. A haze of white fog had rushed in, replacing the entire setting with a blank wall of emptiness — a vast nothingness that seemed almost alive, almost as if it was watching him. Closely. What if the door was locked? Panic gripped his heart. Then, the door was open. Meno male, he muttered in half-forgotten Italian from his parents. He stepped inside and closed the door. Except. Except he found that he was not back in the hallway. Goddamnit. This house was getting on his nerves. Ginger was nowhere to be seen — but the boy was there, young Freddy. He sat cross-legged in yet another room, motionless and fixated on the ouija board laid out in front of him on the bare wooden floor. He held the small wooden planchette in his fingers and muttered so quietly Mantegna could not make out his words. His eyes were clamped shut and his face scrunched with effort. Freddy looked older than he did at the time of the car crash. Like all the apparitions Mantegna had seen in the house on Edgar Lane, the boy seemed not to notice him. Mantegna approached the now teenage Freddy. He leaned in to hear what Freddy was whispering — heard him say, “Ginger, Ginger,” repeating her name like a mantra. He lifted the planchette to his lips, hot breath on the small wooden object. He carefully placed the object on the board always repeating his sister’s name. Mantegna crouched and drew a circle around the boy and himself. He had no chalk or salt — indeed, no means of actually marking the circle, so instead he concentrated on visualizing the trail of energy left behind by his finger. To his astonishment, when he closed the circle, the invisible boundary flared up with a blueish luminescence. Mantegna sat cross-legged and placed his hands on the planchette alongside Freddy’s living fingers. He felt a slight shock when Freddy’s eyes seemed to momentarily meet his own — and then it was over and Mantegna wasn’t sure if it was merely a random glance or something more. Like maybe Freddy knew he was there. Freddy cleared his throat, “I wish to speak with Mantegna the Psychic.” Mantegna was stunned and he suddenly felt hot, as if he might be sweating. “Mantegna, are you there?” the boy asked. Mantegna slowly moved his fingers, keeping contact with the planchette, and moved his hands towards YES. Freddy’s eyes really did open then, wide and dilated as he watched his own hands follow along with the planchette as it responded to Mantegna’s nudging. “Have you met my sister?” YES “How is she?” W-O-R-R-I-E-D “About what?” Y-O-U “I know she blamed herself for what happened,” he choked, “tell her that it wasn’t her fault.” Mantegna wished for ouija emojis. Where was the thumbs up? He spelled it out: O-K A few tears fell from Freddy’s eyes, rolled down his nose and splashed onto the board. “Tell her I survived will you? — that I’m ok.” He survived? Not according to Ginger. A sharp pinch on his bicep interrupted his thoughts. No one was there — and yet, there it was again. Now a hand gripped his shoulder — shaking him. Freddy continued to speak, “She pushed me clear of the car,” he said. Somehow he sensed Mantegna’s distress. “I can feel you fading,” he said, “Just promise me you’ll tell her.” O-K “Goodbye Mantegna,” Freddy said. He let go of the planchette. Mantegna moved the device of his own accord, giving it a sharp blow that should have sent it flying across the room, but instead nudged it hardly an inch to the bottom of the board, where is came to rest on: GOOD BYE Freddy seemed to freeze in place and Mantegna felt the unknown force shaking his arm. He was gripped by an almost irresistible need to flee the room. He fought the urge and proceeded to the door in measured steps and it seemed to Mantegna that Freddy’s eyes shifted, tracking his progress as he broke the circle and reached for the doorknob. In the hallway again and the lights were flickering — the blue softening to a warmer orange then back again. This invisible assailant was shaking him by both arms now. He careened down the hall like a pinball bouncing off the bumpers until at last he crashed through a door into the séance room — and there he was — sitting in his chair, as serene as the Happy Buddha, while Ginger was in the process of shaking the living daylights out of him. “Wake up,” she cried anxiously, “wake up.” He felt himself sucked across the room with a slurp like water down a drain. Now he was in his chair. He felt like he was being manhandled — in fact, he was being manhandled. He felt certain she was considering slapping him. The thought of a loud smack across his face made his eyes fly open. “Ok, ok” he said, shielding his face, just in case she really did wind up a slap. “I’m awake.” “Oh thank goodness Mr. Mantegna,” She flopped down in a chair next to him. “I thought you might be lost.” “Lost in the house?” “Yes, it is awfully big,” she said, “Don’t you find?” A shiver travelled his spine when he recalled facing that terrible void on the steps — the feeling of the Abyss staring back. “After the car accident you vanished,” he said to change the subject. “I woke up back here,” she said, “Where were you?” “I met your brother.” “Freddy?” her mouth trembled. “Was he —” He told her about the incident — the ouija board, the circle, Freddy’s story — and the message. “He said he survived the crash,” Mantegna said, watching her carefully. “He said you saved him.” “Saved him?” “You pushed him clear of the car.” She broke down at the words, “Oh my god,” she said, her hands over her face, sobbing. “After all these years,” she hugged Mantegna. “At last I know.” When she released him, Mantegna was glad he was still sitting. Young Ginger was back. Seeing his look of confusion, Ginger smiled. “When I saw the car about to hit Freddy I pushed him as hard as I could,” she said. “I didn’t see if he was clear of the car or if it hit him — but, well, it did hit someone. It hit me. I died in the hospital — and this is how I appeared on that day.” “You died?” She nodded, “Then, I somehow found my way back here, back home. I needed to know if I saved him — before I could move on.” Mantegna understood, he had met an obsessive ghost or two. She continued, “I was never able to find Freddy and instead I was lost in this house.” “For more than sixty years?” “I wandered these halls for all those years. I eventually realized I would need a real psychic to guide me to my brother. So I waited — and, one day it happened. I sensed your presence. Your light was like a beacon for me and I knew without doubt that I could find you. So I reached out through the phone. Then, when you came, I simply took on my adult appearance — as I would have looked had I survived.” “Your brother survived the crash thanks to you,” he said, “but you were killed when you saved him.” He was starting to piece things together — and his father said he would have to get by on his looks alone. Take that dad. “I think you shared a link with Freddy and, even though you were never able to directly communicate, somehow you both found me. Somehow you both knew.” By then she was already fading away. “Maybe you’re right Mr. Mantegna,” she said. She turned to walk towards the door. “However it happened, we are eternally grateful,” she said. She left the room and the door gently closed. He heard her footsteps dwindle as she walked down the hall. “Thank you again,” she said, her voice faint and distant. “Goodbye.” “Goodbye Ginger,” he said and as the words left his lips the illusion that had cloaked the house seemed to be lifted like a veil from his eyes. He found himself seated. Same chair. Same room. No lights were on and the furniture was covered with large faded sheets. A haze of dust permeated the atmosphere and covered most everything like the faint layer of an early November snowfall. He was still musing over these events some weeks later, as he sat waiting to meet the lawyer. Soon he was ushered into her office — she was perhaps sixty and wore a pair of those wireframe glasses that Mantegna always associated with smart people. “Mr. Mantegna,” she began, glancing down at a stack of dog-earned papers on the table, “I have to admit, this is one of the stranger requests we have ever accommodated.” She peered at him through those glasses. “By the way, are you Mantegna — the Psychic?” Mantegna smiled modestly and allowed that he was. It turned out, she explained, that he had been named as a beneficiary in the will of one her clients — Freddy Rogers. He was very wealthy and had left a small property to Mr. Mantegna. The value of the property was insignificant next to the overall worth of the estate and the family hadn’t objected. The strange part was that the inheritance had been held in trust from Freddy’s passing until this very date — nearly forty years. For all those years her firm — she herself in fact — had maintained the property in accordance with Freddy’s wishes. She had been his last lawyer and he her first client. Together they had drawn up the will all those years ago On her very last meeting with her long deceased client all those years ago, he had given her a simple message to pass on to Mantegna — just that he wanted to say thank you for everything, both from himself and from his sister. All these years the mystery had gnawed at her. Mantegna and Freddy had never met. In fact, he hadn’t even been born when Freddy passed. Now that he was here, in front of her, she just had to ask why? How? He knew he could leave with a smile and a handshake — but that wasn’t his style. Reticence just wasn’t his thing. He told her the whole story. Every last detail. The phone call. The séance. The rooms. The ouija board. When he was done, he didn’t know if she believed a word of it. She had a strange look in her eyes though, she really did — a strange look indeed as she handed him the keys to Number 7 Edgar Lane. He left his card, as always— because you just never know — today might be the day you need a psychic. |

Podcast HostLinda Gould hosts the Kaidankai, a weekly blog and podcast of fiction read out loud that explores the entire world of ghosts and the supernatural. The stories are touching, scary, gruesome, funny, and heartwarming. New episodes every Wednesday. |